The Reluctant Director

The Reluctant Director

by Chris Mares.

I am, by nature, a teacher. I enjoy people and showing people how to do things, whether it’s playing a sport or learning how to speak, read, or write in English. I’m also good at thinking on my feet and being creative. As a result, I have always loved to teach.

Administration, on the other hand, has never appealed to me. I say this having been the Director of the University of Maine Intensive English Institute for almost twenty years. Quite frankly, it was not worth the extra five thousand dollars I was paid annually as a stipend.

During my second year at the University of Maine, the Director of the Intensive English Institute gave two weeks’ notice and left. And there we were, a rudderless ship. Not wanting us to sink, I visited the Dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and volunteered to keep things going until a new Director was found.

Two years later I was made interim Director and two years after that, Director. I had no background in management and no idea how the financial aspect of the job worked. The situation was compounded by the fact I was given no training. It was sink or swim.

The first thing I noticed was the change in my relationship with my former peers. I was now the boss and was viewed differently. The second thing I noticed was that I was usually the last person to hear about things concerning either students or teachers.

I’m a people person and I like to be liked so I didn’t enjoy the new separation I was experiencing.

And so my journey as Director began. Here’s a brief list of some of the things I am not good at: confrontation, giving bad news, attending to financial details, sitting through long and tedious meetings with the other chairs and directors.

Admittedly the title Director had some cache and it helped get some things done, but could I have lived without being the Director? Yes, absolutely.

I did learn some things about people. For example, if you are easy-going and cut people slack in terms of office hours, they really resent it when you try and rein things in.

The previous Director ruled with an iron fist. She was unpleasant, demanding, and lazy. She would take all the credit for things that went well and place the blame squarely on others’ shoulders when they didn’t.

This changed when I became Director and perhaps things became too relaxed. I allowed babies and children to be brought to the office. And dogs. I didn’t insist that teachers were at their desks when not teaching. The result was a complete change of atmosphere but whenever I attempted to tighten things up, I could sense a creeping resentment. I was learning that when you are the manager, you are, however good you are, the enemy.

I should say that now I am a teacher. I spend fifty percent of my time teaching in the IEI and the other fifty percent in the Honors College. I am in paradise. Teaching brings me nothing but joy and when I look at my friends who are administrators I do not see content people.

Administration requires a great deal of time and effort and a considerable number of meetings. One is viewed with a degree of suspicion when one has the power to hire and fire.

It was only out of concern for my job as a teacher that I volunteered to take the helm. In my latter years as Director I gave myself an almost full teaching load in order to minimize the amount of time I had to administrate.

My only positive observation is that the University has made efforts to hold training sessions for managers, which were quite useful.

Quite why a teacher would leave the classroom to become an administrator is beyond me. Peers of mine have become Chairs, then Deans, and even the Provost. None of them look any happier. They tend to dress more smartly and have notably larger salaries.

When my students ask me what I plan to do when I retire, I tell them that (a) I don’t plan to retire, and (b) if I was forced to retire I would volunteer to teach.

Teaching is my calling. Managing isn’t.

Ideas and emotions: Finding a space for sharing

Ideas and emotions: Finding a space for sharing So, is it Imposter or Impostor?

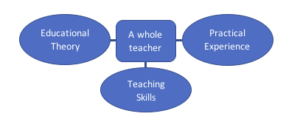

So, is it Imposter or Impostor? Teaching for years in Japan without a recognized teaching qualification or teaching license from Canada always left me feeling somewhat insecure, with a sizeable “gap” in my overall identity as a teacher. Even though I was amassing thousands of contact hours in the classroom, had very good communication skills, continually learned from my many mistakes, and could always fall back on my natural enthusiasm to get students to work with me more than work against me, I always carried a doubt that maybe all of those teachers who earned an actual education degree knew a secret that I, the imposter, would never discover.

Teaching for years in Japan without a recognized teaching qualification or teaching license from Canada always left me feeling somewhat insecure, with a sizeable “gap” in my overall identity as a teacher. Even though I was amassing thousands of contact hours in the classroom, had very good communication skills, continually learned from my many mistakes, and could always fall back on my natural enthusiasm to get students to work with me more than work against me, I always carried a doubt that maybe all of those teachers who earned an actual education degree knew a secret that I, the imposter, would never discover.

Two Conversations About Teaching

Two Conversations About Teaching