Road Posts Along The Way

Before I started working at my current high school, the man who interviewed me tried to impress upon me that the students were, “a bit of a challenge.” They were futoko, which, he explained meant that they had missed over 30 days of a school year, not because they were truant, but because… and then he ticked off a laundry list of reasons. They had been bullied. They had anxiety disorders. They were diagnosed with light cases of Aspergers. They exhibited behaviors like mild self-mutilation. They had been victims of domestic violence. He looked at my resume, mentioned that he was happy I had social work experience in Chicago, shook my hand and offered me the job. Funny thing, my social work experience hasn’t actually been all that helpful. Not when I started and not now, five years into the job.

Now I know that futoko can be translated as school refusal syndrome. I’ve also taken in-services and learned that many futoko are labled in some way or another (ADHD, DD, LD), a garden of capital letters blooming throughout their school records. But being able to decipher a school record hasn’t taught me much about how to meet the needs of my students. Fortunately, my students are willing to tell me what they need themselves. All I have to do is pay attention to how they stand up for each other, and how they care for each other.

Here are six things that my students have taught me about how to create the kind of safe space that can foster learning in a classroom. There is no particular order to this list. On some days some things are more important than others. Some of the ideas on the list might even seem contradictory. That is because they are. Learners are people. There’s no manual for how to connect with people and there’s no map for how to go about learning. Still, a few road posts are better than wandering around lost.

1. Make every success a group success. My students all progress at different rates. Some get stuck for weeks without any sign of improvement. Some suddenly switch on and take in months’ worth of language in a few days. But when one of them passes a standardized test, wins a speech contest, or gets into university, they all celebrate. Because they are a language community, I do everything I can to foster this feeling. Learning to celebrate these successes—big and small—helps all the students feel as if they are moving forward. It is the tailwind that keeps them learning.

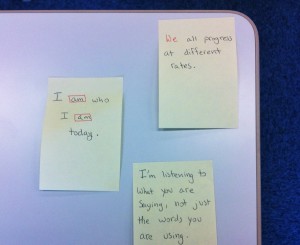

2. Honor and welcome who my student is today. Yesterday and maybe for the whole month before that, one of my students might have taken notes, been active in class, and flashed smiles here and there. But today a cloud hangs over his head. He can’t put together a full sentence. Maybe he doesn’t answer back when I say hello. Still, he is in school. He managed to pull himself through whatever darkness greeted him when he woke up in the morning and got himself to class. Thinking about what he could do yesterday is not going to help him do any better today. One of my students’ most common greeting to a friend in a funk is a simple, “I’m glad you’re here today.” It is a great greeting. I would even put it slightly ahead of “nice to see you,” on my list of useful phrases.

3. Focus on the language, not the person. My students have been bullied, pushed out and ignored. When they share something about themselves, it is a gift. When they correct each other in class (and they sometimes do), they have a way of saying a word and waiting for a few heartbeats for their classmate to respond. That one word and pause seems to change the gears of the conversation. It shifts it out of the personal. Now I try and do something similar to separate the content from the language and make the class feel safer. Jotting down student language on Post It Notes, correcting it, and laying it down on their desk is one way I’ve found to help depersonalize the language of a communicative act.

4. Focus on the person, not the language Often as I watch students have a conversation in my class, one of them makes a shocking grammatical error, and the other student does not comment on it at all. I think this probably has something to do with students’ ability to differentiate between an error, a mistake, and a slip. If you put the jargon aside, it is really about how sometimes people just can’t put together a decent sentence—in a second language, or even in a first. Depending on what else is going on with the person, sometimes those errors/mistakes/slips do not really matter very much. So on those kinds of days, let a student talk, and instead of checking for cracks in the surface of their words, dive a bit deeper down towards their intentions.

5. Have more patience for students than they have for themselves: Missing 30 days, 100 days, 1 year, or 3 years of school can make anyone feel a little stressed about lost time. Compound that with a diagnosis that implies the future is less than well paved and it is no wonder my students get a little impatient with themselves. Fortunately, most of the students in class are in or have been through a similar situation. Perhaps that is why they never, ever, get impatient with each other. As the teacher, I’ve learned to take it a bit more slowly, extend my class wait time, and give hints as necessary until a student can answer any question I ask. Someday I hope to be as patient with students as they are with each other.

6. Ignore general lists of things that should or shouldn’t be done for students. When talking with one another, my students have no such lists in mind. As far as I can tell, they also have no intention of making one, which seems to me to be a very good thing indeed. Watching them support, share, and relate with each other from moment to moment is the best way I’ve found to keep learning what it means to be the kind of teacher I need to be—for them and for myself.

6. Ignore general lists of things that should or shouldn’t be done for students. When talking with one another, my students have no such lists in mind. As far as I can tell, they also have no intention of making one, which seems to me to be a very good thing indeed. Watching them support, share, and relate with each other from moment to moment is the best way I’ve found to keep learning what it means to be the kind of teacher I need to be—for them and for myself.