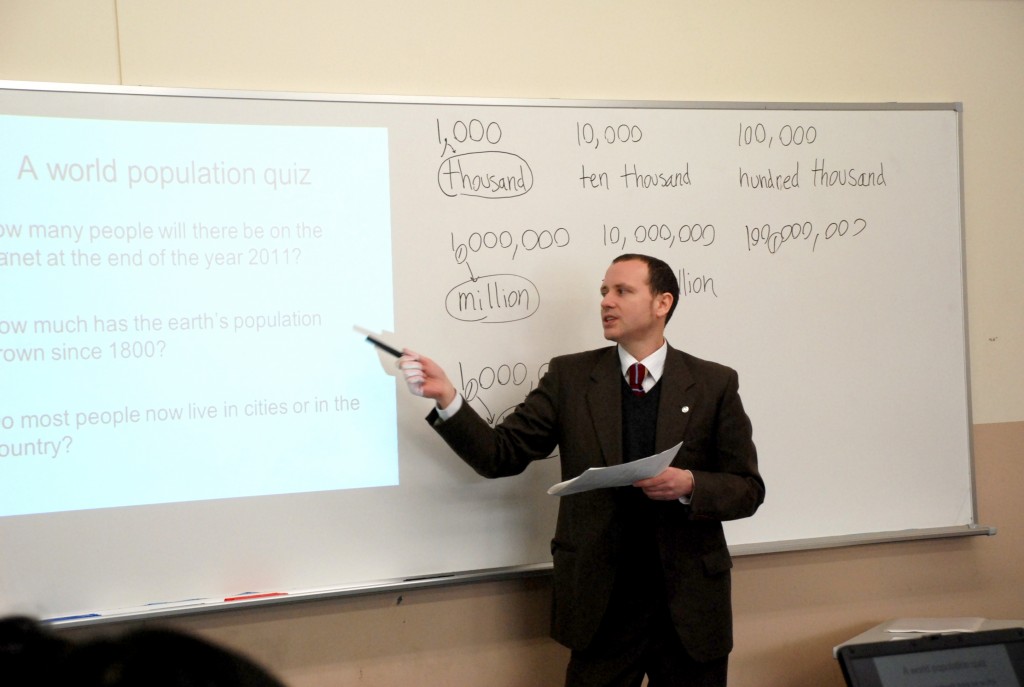

Academic Director

Rules Are Made To Be Broken — Scott Thornbury

The first rule that I broke as a new teacher was using translation in class. I can’t remember being told not to, but everything on my initial training was geared to a direct method, no mother-tongue, kind of methodology. Moreover, translation was considered an unreliable means of conveying meaning, given the differences between languages and cultures. One person’s clock is another person’s watch, so it’s better to use a picture of a watch than to say ‘watch’, lest the students think it is a clock, or vice versa. For these reasons, translation was considered to be a highly sophisticated skill, only to be tackled with the most advanced students.

“The use of the students’ mother tongue need not be a taboo, and that in fact it can be exploited as a very natural prompt for real communication”

But I did it with beginners. I was teaching in Egypt, and had to teach a lesson on basic description using there is…/there are…, adjectives, it’s got… it hasn’t got…, and so on, the theme being towns and villages. The towns and villages in the coursebook did not look like the towns and villages the students were used to, so I had a problem. I wanted to base the lesson around the kinds of village that my students would visit when they went home for the weekend, villages with mosques, sugar factories, covered markets, and maybe the odd Pharaonic monument. I would have used a picture of one had I had one, but I didn’t. So I had this idea of asking the school receptionist, who I knew came from Upper Egypt, to describe her village onto a tape, and to do it in Arabic. I hardly spoke any Arabic and I used this to my advantage. I took the tape into the class and asked my beginners to help me make sense of it. More than information gap, there was a language gap, and they were eager to fill it. I played it line by line and they shouted a rough translation at me, using mainly words rather than structures: “Mosque! Ferry!” and so on. I would stop and reformulate what they were telling me onto the board. It went something like this: “My village is very nice, it’s very quiet, it’s on the Nile, there is a large mosque in the centre, there is a sugar factory, there’s a primary school but there isn’t a secondary school. There is no university either. There is a ferry across the Nile.” And so on. By the time we had translated it reformulated it and put it on the board we had all the structures we needed for describing a town or village. And for practice, of course, they described their own villages – not so very different from the school receptionist’s.

“I learned that rules are made to be broken, and even if the resulting experience is not as productive as my Egyptian village lesson, you can always learn something from experimenting”

What did I learn from that lesson? That the use of the students’ mother tongue need not be a taboo, and that in fact it can be exploited as a very natural prompt for real communication. Nor is translation necessarily a very sophisticated skill – as we now know, thanks to online translation tools. I also learned that rules are made to be broken, and even if the resulting experience is not as productive as my Egyptian village lesson, you can always learn something from experimenting.