Seeing Through The Cracks

How we can see our class more clearly in real time — Kevin Stein

In general, people are pretty miserable at seeing what is going on around them. Just check out this video of Joshua Bell, one of the best violinists in the world, playing in a DC metro stop.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hnOPu0_YWhw&w=560&h=315]

If you’re interested in why this happens, I highly recommend Daniel Simons The Invisible Gorilla web site and his work on inattentional blindness. But do teachers in their classroom suffer from the same kind of blind spot? In general, I would have to say no. Part of the reason is teachers develop lesson plans. That means we are usually comparing what is happening in class to those simulated lessons in our brains, and things that don’t happen as we expect stand out rather clearly.

Ironically, this habit of focusing on what seems to be going wrong—or even what seems to be going right—can also keep us from seeing what is really happening in our classes. Just the other week, I had told students that they were not to use their electronic dictionaries in class. When I noticed a student with a dictionary on his desk, the only thing I could think to say to the student was a snappish, “Put that away.” I felt like a jerk when the student explained he was using the dictionary’s voice recorder function. Aside from my assumption that a physical dictionary on a table equals looking up words, I was also running up against the constraining effects of the activity’s original conceptualization. The dictionary on the table becomes a problem because it does not fit in with the original idea of how the activity should work. In this situation we miss what might be creative solutions (students can record a class to look up words later) or opportunities to further expand and enrich the classroom experience for our students.

Fortunately, there are some simple things we can do to allow us to get a fuller picture of what is happening in our classes.

Change perspective: If you are standing next to a group of students who are working and something seems off, walk across the room and view what is going on within the larger context of the class. What seems strange or off-task from close up might suddenly feel a little more acceptable within a bigger picture.

Take a personal time out: as teachers, we want to fix perceived problems as soon as possible. But perceived problems might not be actual problems. People in stressful situations—such as an activity, which seems to be falling apart—tend to make decisions with only partial information and rarely think about alternatives in systematic ways. Giving yourself an extra minute or two to just watch what is happening can lead to better outcomes if you do decide to intervene.

Keep a real-time journal detailing what you see, not how you feel: by focusing on what your students are actually doing, you increase the chances of noticing potentially useful tweaks to an activity you would have never come up with on your own.

Ask non-confrontational questions: If you want to know what students are doing, just ask. Students, who seem to chatting in L1 when they should be practicing a dialogue, might actually be divvying up roles.

Use dictation as a class observation tool: just because students start an activity by doing what you expect, does not mean they understood what you said. Take a moment to have students put down on paper what they think you said or what they think they should do. While it is disheartening to find out students hear “Choose a book,” as “Juice a book,” it also gives you an opportunity to get things back on track before they completely fall apart.

While there are things we can do to be better observers of what’s happening in our classrooms, we can’t completely overcome our limitations as humans. This is why inviting a co-worker in for supportive peer observations and video or audio taping and transcribing your classes can also be very useful. We have to try various ways to see what is happening in a lesson in real time because it is in the often hectic and bumpy minute-to-minute of classroom life that our students are waiting, right there in front of us, hoping to be seen.

Connect with Kevin and other iTDi Associates, Mentors, and Faculty by joining iTDi Community. Sign Up For A Free iTDi Account to create your profile and get immediate access to our social forums and trial lessons from our English For Teachers and Teacher Development courses.

The beauty of questioning is that it helps you look deeper into yourself. Questions ask you to investigate, to doubt, to grow, and to change. Questions help you learn to see.

The beauty of questioning is that it helps you look deeper into yourself. Questions ask you to investigate, to doubt, to grow, and to change. Questions help you learn to see.

For several years, I’d finish classes and head to Ginza to wander the streets. I can honestly say that I’ve never been lost in Ginza– until this morning.

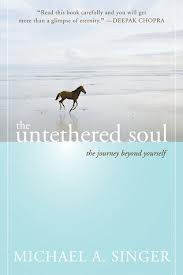

For several years, I’d finish classes and head to Ginza to wander the streets. I can honestly say that I’ve never been lost in Ginza– until this morning. I’m reading a book called The Untethered Soul by Michael A. Singer. In this book, Singer writes about the voice inside all of us, about how that voice can get us to believe it is who we are and is reality itself. It’s not. “What voice?” I can hear you asking. Say the word “hello” silently in your mind. Make your inner voice say “hello” several times. Hear that? That voice. Make it shout “hello” inside yourself. Make it say, “I’m not good at ______.” No, stop. Don’t complete that sentence. Make the voice say, “I’m really good at ______. Complete the sentence in different ways. Listen to yourself. Now, think about this.

I’m reading a book called The Untethered Soul by Michael A. Singer. In this book, Singer writes about the voice inside all of us, about how that voice can get us to believe it is who we are and is reality itself. It’s not. “What voice?” I can hear you asking. Say the word “hello” silently in your mind. Make your inner voice say “hello” several times. Hear that? That voice. Make it shout “hello” inside yourself. Make it say, “I’m not good at ______.” No, stop. Don’t complete that sentence. Make the voice say, “I’m really good at ______. Complete the sentence in different ways. Listen to yourself. Now, think about this.