Truly Integrating Technology — Nour Alkhalidy

I am a computer teacher who works at a school in a poor village where technology is kind of a big deal. Some of my students don’t have access to the Internet in their houses. Many do not even have a PC at home. At school, some teachers don’t know how to use computers. Others only utilize them in some way. It is rare to find teachers who are really integrating computers and technology into their classrooms. I am one of the few who is trying to do this. I have been working at this for eight years.

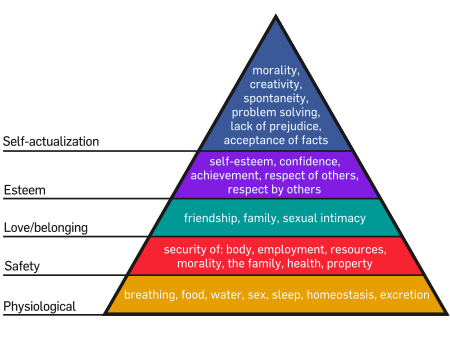

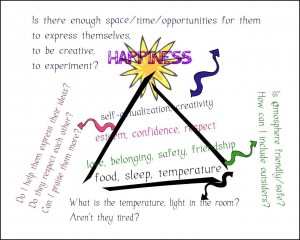

Being a teacher who is trying to integrate technology in such a context has been a little bit challenging for me. Still, although I have had some discouraging moments, my mission has been and is to create a rich environment for my students by introducing new technologies into my classroom – technologies that actively engage and motivate learners while helping me successfully deliver content.

Before planning to integrate a new technology I always consider two issues: my students’ weak basic computer skills and the school’s limited Internet access. Given these parameters, I always look for simple tools that can be used offline. As I design my lesson, I think about how a simple tool can be used to enhance clear curriculum goal and try to incorporate a strategy (often a cooperative strategy) related to such a goal. Then I design activities, making sure each separate group within my class has a task or problem to solve. I also think through how much time a task will take, what roles each student in each group will have, what instructions to give, and what the final output will be.

Personally, If the technology tool I have chosen fulfills subject content goals, improves computer, thinking, and collaboration skills, engages and motivates students, and more importantly convinces me that I cannot proceed without it, then for me I have successfully integrated technology in my classroom.

I usually prepare my lessons using Powerpoint — the old tool that will never die — to explain tasks and instructions. Sometimes I use it as a learning tool to design a virtual tour or micro-lesson.

I also use Microsoft’s FrontPage to design webquests, online scavenger hunts or 5Eonline research modules. Multi-media tools, mindmaps and word cloud applications are also at the top of my technology list to promote visual literacy.

For project work, I tell students they can bring their parents’ cell phones to class in order to capture pictures, record their voices and do interviews. We also use cell phones along with Microsoft Photo Story or Movie Maker to create videos that showcase work, summarize ideas, display knowledge on a subject, or share thoughts about the project we’re doing. They also use cell phones to gain internet access that allows them to extend their learning by finding additional information they then add to a FrontPage website made by them.

I’ve been involved in some global projectson Twitter like Michal Ann C’s (@Cerniglia) Sharing Perceptions Project in which my 9th grade students in Jordan shared their thoughts about the U.S. with Michael-Ann’s 6th grade students. In Jordan, my students and I used Tagxedo and Wordle to present brainstorming ideas, and Vokito express our thanks for being involved in the project.

Sometimes, I have 10-15 minutes at the end of a class for a group game. Playing games enhances students’ attitudes and motivates them. For example, a simple game like FreeCellor Tetrisoffers some opportunities for group collaboration and improving thinking skills, while a Rapid Typing Game improves basic computer skill and kills classroom boredom.

I may not have iPads, iPods or laptops in my classroom and my students aren’t adequately digitally savvy learners equipped with the needed skills, but I certainly believe that any technology can be powerful — even the simplest one if it is being used in the right way. It’s not about what tool to integrate but how to exploit its effectiveness and add real value to the learning process.

As a computer teacher, my role is to mainly help my students benefit from technology’s opportunities, improve their computer and information literacies skills (along with other 21st century skills), and finally to reduce the big gap between what the world is like in my poor village with the life my students will have in college and beyond. If I can do those things, then I consider all the challenges I face worth every effort.

Connect with Chuck, Scott, Tamas, Vladimira, Nour, Ann and other iTDi Associates, Mentors, and Faculty by joining iTDi Community. Sign Up For A Free iTDi Account to create your profile and get immediate access to our social forums and trial lessons from our English For Teachers and Teacher Development courses.

Like what we do? Become an iTDi Patron.

Your support makes a difference.