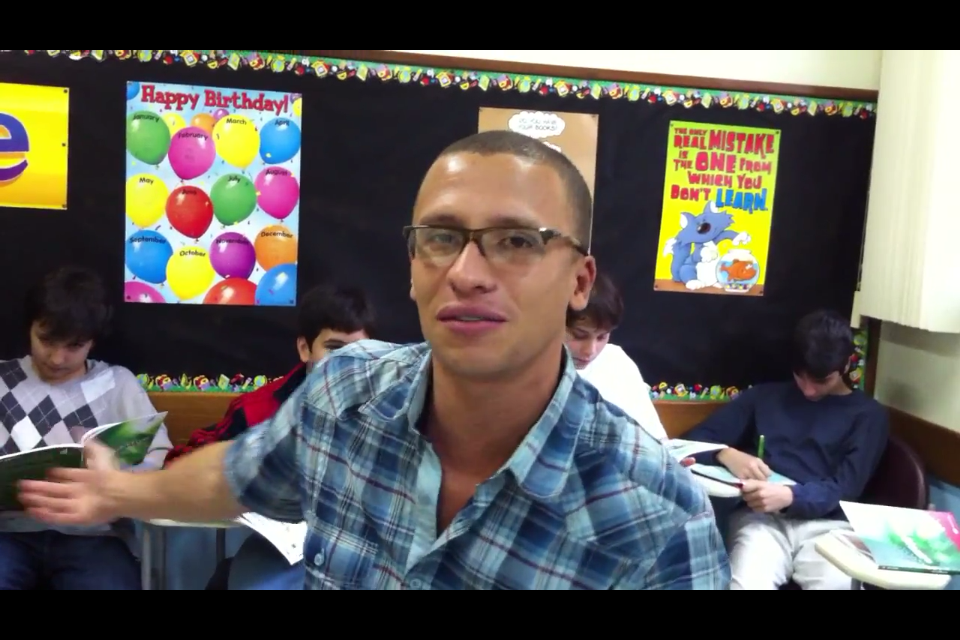

Managing a Young Learners Classroom: Challenges and Perceptions – Bruno Andrade

It goes without saying that children’s classes are difficult to manage. The success of your lesson will largely depend on how well you manage your kids’ behavior. Unfortunately there is no right answer when it comes to dealing with behavior, specially dealing with young people who have not yet developed community and social skills, and who do not have any personal reasons for being English students (they are there because their parents told them to, not because they have a specific goal in mind).

On the course of the years I have been teaching English to Young Learners, I have acquired a number of techniques here and there that might come in handy. First of all it is important to understand a bit more about behavior and your expectations towards it:

What kind of behavior are you aiming at?

– Behavior, relationships and learning walk hand in hand: Good and pro-active behavior is a result of learning and good relationships as wells as a strong influence on how kids learn.

– School Staff, Teachers, Parents and Students have a different understanding of behavior: When new to a school, teachers must learn the behavior policies that permeate the school’s system and have a brief notion of problematic students/classes with past teachers. Besides that, sharing insights about behavior with parents is crucial since they need to have a grasp of the way in which home standards are hindering or helping their children’s learning at school. It is also of utmost importance that teachers share insights about behavior with students, this will surely equip them to ponder about and understand what makes people act they way they do. It can also build on their abilities to take responsibility for their behavior and to help each other behave better. A common understanding will not only provide a solid base for the school at large to promote good behavior but also to respond to inappropriate behavior.

What can you do to help better manage your YL class?

1 – Help children to take ownership of their behavior: collectively draw a Dos x Don’ts poster on the very first day of school. First elicit from students what they can do and then move on to the more serious part (donts). Do not ignore any contribution from students. Put them all on the poster but use a bigger handwriting or font for the ones you consider to be serious breach of the “contract”. Display the poster on an inside wall and refer to it whenever students break any rule. After some time you shall see that there will be no need to refer to them when students misbehave. If they don’t realize it, their peers will promptly remember them of it.

2- Don’t be nice (at least not during the first week!): Start being firm and demanding with your little ones. Loosen up little by little so that your students believe that they earned your heart (even if they already had). This way they will value more the relationship you share and thus behave well when expected. Rapport is key to the development of a healthy relationship between students and teachers. You don’t have to love your students (and that goes for any age bracket), you must respect them as human beings. Learn their names fast, this way you will be showing that you care about them. Learn about what your students do outside school, their abilities, likes and dislike. Plan your lessons having your students in mind and always bring something that will surely call their attention to the class and motivate them continuously. Praise your students for quality of work and especially for effort. Use praise to encourage students as well.

3- Vary activities but maintain a routine: Young Learners need routine. Establish a routine for giving instruction. Preferably stand at the front of the class, using lots of body language and eye contact. Move around in other stages of the lesson so that you can see and listen to all students. Constantly change seating arrangements. Draw the design you want on the board and have students sit accordingly. Seating arrangements can help you set students apart on purpose or maybe unite a stronger with a weaker kid so that they work collaboratively. Surprise activities may become a card up your sleeve. Use them in order to change the pace of your lesson in case students get too excited. When moving from one activity to another, avoid screaming for attention and silence. Develop a signal that they will recognize and follow suit. E.g: turning off the lights or using a bell or any instrument such as a rattle or tambourine. Always have extra activities ready on your table for fast finishers. Never leave any student without something to do. Keep them busy all the time.

Teaching YLs Is No Easy Task.

The more we study about and work with them, the more we find out we still have to learn. As simpler as these strategies may seem, they can hopefully provoke a big impact in your teaching. Nowadays in the ELT market a good Young Learners teacher is seen as a multiple skilled professional who not only has the expertise and flexibility of a teacher but who is also sensitive enough to perceive, deal and work on the developmental differences that happen in every kid. These include cognitive perceptions and variations, motor skills, social, psychological and emotional characteristics. A photographer named Robert Capa once said that if your pictures aren’t good enough, it is because you aren’t close enough. The same goes for your kids. Get to know them better and you will see how drastically your lessons will improve.