by Jessica Brook

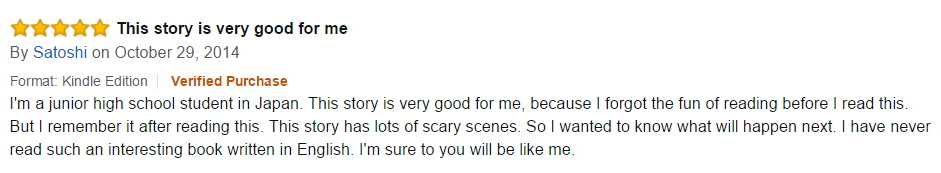

by Jessica Brook

“Doing a project that is truly complex and difficult tests your real ability… the thing we most fear with regard to failure is our own self-acknowledgement, that we really don’t exactly know what we’re doing.” Milton Glaser

This time last year, I was halfway through my first proper Action Research enquiry, and I definitely didn’t feel like I knew what I was doing. Three years after finishing the DELTA I had been itching for a new challenge. Although I was very keen to start a master’s, I wasn’t so keen on 2+ years of distance learning. Looking at various MAs online I came across a new course with the University of Leicester, a Post-Graduate Certificate in Action Research, a much more doable seven months. I was a stranger to formal research, although throughout my teaching career I’ve tried hard to develop through reflective practice. Indeed, this is what has always kept it interesting, so I was really motivated to step it up a level.

Nine months later, frustrated and dissatisfied, I was secretly pleased to see the back of it. I felt that nothing I’d set out to discover had been clarified as I’d hoped, and if anything I just had more questions. However, with time and reflection, I began to realize just how valuable a learning experience it had been. I’m now infinitely better-equipped to run small-scale research, to guide and encourage other teachers in their own development.

Bearing in mind the many hiccups I experienced along the way, this is the advice I would give.

- Choose a (good) research question.

An excellent bit of advice my tutor gave was “it’s better to write a lot about something small than the other way round”. I completely disregarded this advice, my research question involving new paradigms in listening instruction, and how best to incorporate them in general English syllabi, as well as teacher training. In hindsight, picking just one technique would obviously have been much more manageable. Posing your research goal as a question helps to focus, but the size of the project inevitably grows with its ambition. So think carefully about what you want to explore, how much time you want to commit, and whether your area of focus overlaps with your students’ needs, your colleagues’ interests, and/or the goals and objectives of your institution. Does it solve a problem? Or respond to a student survey? You’re also more likely to gain support this way. Mine admittedly did all three, but would have been just as useful on a smaller scale.

- Don´t get rid of anything.

What’s the difference between bog-standard Reflective Practice and Action Research? This debate continues to rage in academic circles and some would argue there isn’t a distinction. However, if you’d like to take your findings to a wider audience, be rigorous, and keep an open mind. It’s very easy to start off unconsciously expecting a particular outcome, but things may well not turn out that way. And it’s within the ”mess” of Action Research that interesting things happen. You won’t know if you don’t have the data to explore, so with that in mind, record everything, chuck nothing. One of my most unexpected and interesting insights came from my field journal. Meant as a personal record, it became a rich source on the different, often conflicting, roles we take on when facilitating planning, observation and feedback sessions.

- Individual, collaborative or participatory?

Thinking about who you want to involve is really important. Collaborating with colleagues is extremely rewarding, but bear in mind the practicalities. Put together a schedule detailing the main commitments with time estimates and communicate it in advance. Getting students to participate in the process empowers them – after all they’re at the heart of what we do – but make sure they know exactly what’s involved, seek permission, document it. Again if you have any plans to take your findings to a wider audience (i.e. outside your own school), this ensures your research is ethical. I decided on a collaborative approach known as lesson study. Working alongside two other teachers was intense and challenging, but the detailed, positive comments in their exit questionnaires made it all worthwhile.

- Be flexible, expect hitches.

Picture the scene. You and your colleagues spend hours planning a dynamite observation lesson, which you plan to video on the only day that teachers, timetables, and classes align like a once-in-a-century solar eclipse. The lovely case-study students have agreed to give up an hour of their time after class for you to interview them. You arrive that morning to discover all classes have had to be relocated to a nearby hotel due to noisy building work. The said hotel has terrible audio equipment and all the plug sockets are deliberately positioned to prevent effective video recording, or so it feels. Unfortunately, these things just happen in teaching. Don’t throw in the towel, do your best, record, and note-take whatever you can. Learn, move forward, and look for solutions.

- Share your findings.

Perhaps my biggest disappointment was that I left the country before my write-up was complete, so I wasn’t able to share it with my colleagues face-to-face. Reporting your findings gives a sense of resolution and regardless of how worthwhile you feel it was, people will appreciate your efforts. It’s also a great way to raise your profile and connect you to a wider community and there are many outlets for doing so, iTDi being just one example. Give a talk, submit an article, start a blog, make a poster for your office!

I’d be lying if I said my project was a complete failure, far from it. In fact, my main failure was not realizing at the time how much more I would learn from the process itself, rather than the final product. Actually, I do have a more fully formed and practical approach to listening instruction in my own classroom, which is what I’d set out to investigate after all.

“There’s only one solution… Embrace the failure!” Milton Glaser

by Theodora Papapanagiotou

by Theodora Papapanagiotou

Over The Wall of Experience

Over The Wall of Experience The Difference an Audience Makes

The Difference an Audience Makes T Stands for Tired Teens

T Stands for Tired Teens