by Theodora Papapanagiotou

by Theodora Papapanagiotou

If we lived according to the dictionary, feedback would be “helpful information or criticism that is given to someone to say what can be done to improve a performance…” In reality, what we do is grade our students’ tests and exercises and point out what was wrong, mark their essays, and write correct answers. That’s what we often call and consider to be feedback. It looks like we use this F-word in a wrong and utterly inappropriate way…

I am afraid that in the majority of school systems the notion of feedback has a lot to do with grades. If the grades are good, the student is doing well. But is this always the case? Does a grade actually show the ability of a student? We realize that each student is different, and their unique personalities have varied interests, likes, dislikes, and ambitions, which all have an impact on students’ learning that we put to test. How can a limited set of grades clearly and extensively determine their abilities? More than that, if grades are the only feedback we give our students, can we ever be sure they benefit from it?

Feedback should not be about how we control the students, nor should the students perceive grades as feedback. It is crucial, at least in my own humble opinion, to monitor our students both for their general performance and results in specific tasks, to praise them for their hard work and effort and, ultimately, scaffold them to new extremes. And then turn to them – do they actually understand our praise, our criticism, our support, our positive and negative feelings?

If we want change, it’s important to involve our learners more actively, make them think critically about their learning and take part in the feedback process. For example, when we tell them how we assess their performance, the students themselves have to realize what’s in it for THEM. Why do they have to learn? Why do they have to do the tasks they do? How do they benefit from these tasks? The answers to these questions might give a bigger picture of learning for both students and the teacher.

A simple and effective way to involve students in their own learning is through working with a KWL chart. I have recently been doing that with my students and trainees and found this technique engaging and beneficial. The chart asks to think and note down answers to three simple questions:

What I Know

What I Want to know (to be answered before the session)

What I Learned (to be answered after the session)

By using this chart, from the very beginning we can activate and assess their schematic knowledge on a subject, not to mention enthuse them and get them curious, motivated and encouraged to learn something new. By the end of an activity or a session we can get students to analyze their learning experience themselves, match their objectives with the results, and in this way give self-assessment.

I believe our feedback to students must be:

- descriptive – describe the problem, do not accuse them of making errors but instead provide with strategies that will enable them to improve and avoid such errors in the future;

- in-time – students need to know how they have done on a task almost immediately! Assess the occasion and decide when would be the most appropriate time to do give feedback. Don’t wait too long!

- sensitive – don’t discourage your students by being overly critical, praise them for their effort instead.

It is our job as teachers to educate our learners on how to evaluate themselves and encourage peer assessment. It is our job to offer opportunities to give each other feedback in group and pair activities. We should teach students how to receive, ponder on and apply the constructive criticism which they are exposed to. We should encourage them to use this technique in all aspects of their lives. Most importantly, don’t forget:

Keep improving – Κeep learning – Κeep moving!

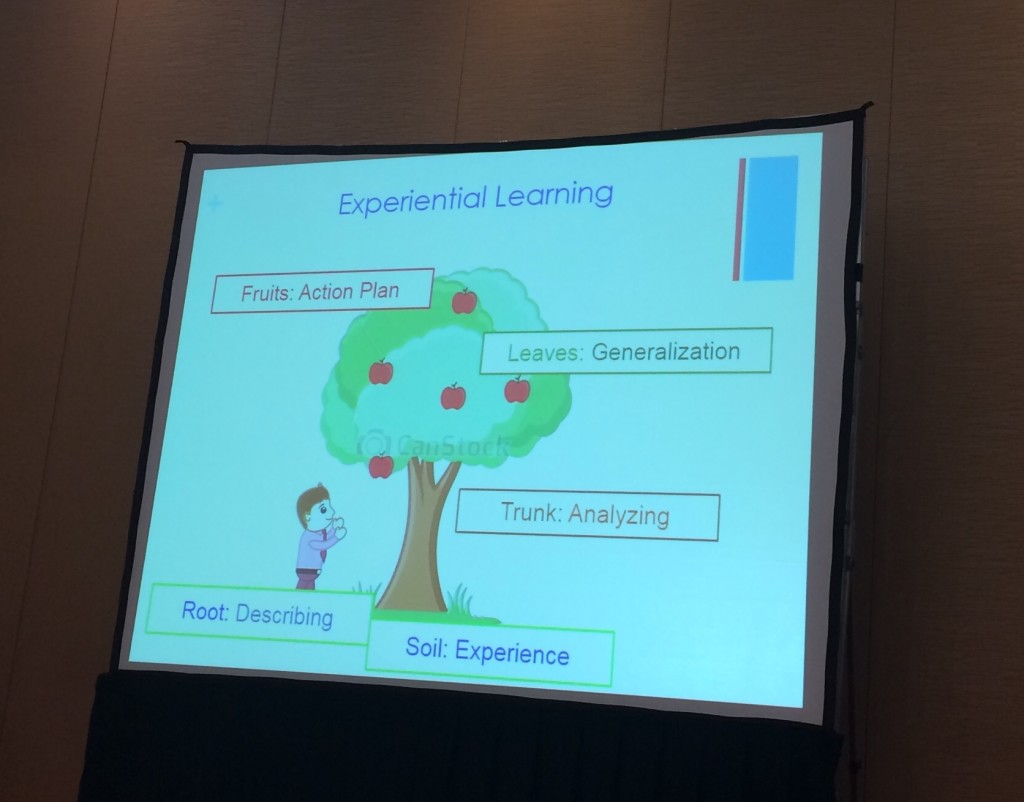

By Zhenya Polosatova

By Zhenya Polosatova

By Patrice Palmer

By Patrice Palmer References:

References:

Breaking the Cycle of Failure

Breaking the Cycle of Failure How Not to Do Action Research

How Not to Do Action Research

by Chuck Sandy

by Chuck Sandy