In the second issue of our blog devoted to Feedback, Kevin Stein, Angelos Bollas and Anne Hendler share their stories of experience on garnering feedback from students and talk about the lessons that a teacher can learn from doing so.

|

|

|

|

In the second issue of our blog devoted to Feedback, Kevin Stein, Angelos Bollas and Anne Hendler share their stories of experience on garnering feedback from students and talk about the lessons that a teacher can learn from doing so.

|

|

|

|

By Kevin Stein

By Kevin Stein

Last year I was lucky enough to facilitate a workshop with a group of iTDi members at the annual JALT conference in Japan. As a group, we wanted to talk about how listening to our students helps to make us better teachers. I shared a bit about my experience of using videos to help garner student feedback about my teaching and class in general.

I started using videos in my classroom about four years ago. My friend and mentor John Fanselow challenged me and the rest of the teachers in my school to video tape a lesson and, at random, transcribe one minute of that lesson. Then we all got together, read the transcripts, watched the videos, and said what we had seen and read. There were no judgments, no ‘that was a great activity’ or ‘you had a lot of positive energy.’ We simply said what we had seen, which led to statements like, ‘When the student is speaking, he is reading directly from his notebook,’ or ‘When you tell the students to stop writing, many of them keep writing for twenty or thirty seconds while you are explaining the next activity.’ These simple statements of fact often led to suggestions which resulted in more productive classes. Suggestions such as having students turn over their notebooks while talking, or writing directions on the board for students to read so that they can move on to the next activity at their own pace.

As useful as it was to hear what teachers noticed when they looked at my class through short videos and the window of a 1-minute transcription, I felt like something was missing, that there was more I could be getting out of these snapshots of my classroom. Then one day, my co-worker Scott brought in a video. In it he clearly asked the students in the class to work together to complete a storyboard ordering activity, one of those cut-up-pictures of a story which have to be put on the correct sequence after reading a text (there’s an example of a storyboard based lesson). In the video, a pair of students happily get down to work and interact with each other a total of zero times. Scott wanders into the frame at one point, reminds them to work together, and wanders out of the frame. For one moment, the students look at each other warily before going back to writing on their own papers. We all watched the video and tried to come up with small tweaks to have the students collaborate more on the activity (give them only one copy of the worksheet; give each student a specific job such as vocabulary master or scribe; turn the activity into a jigsaw puzzle so half the pictures go to one student and half go to the other and they have to describe the pictures in order to put them in order). But after we had piled up this jumbled hill of suggestions, John said, “Why don’t you show the students the video and ask them why they aren’t working together.”

So that is exactly what Scott did. He took the video back to the students — during their lunch break, no less — showed it to them, and asked them why they had decided not to work together. They both said that they just felt that there had been no real reason, aside from the teacher’s instructions, to work together. As they watched the video, the two students described how they decided to put the pictures of the story in order. They both said that they were enjoying the activity and learning something. One of the students mentioned that if they had worked together, they might not have been able to finish the activity in time. What Scott, as well as the rest of us, had thought was a problem with the activity, was in fact no problem at all. Instead of finding ways to force the students to work together, it became apparent that letting the students work individually, or at the very least giving them enough time to work collaboratively (which, as the student pointed out, does often take more time than working alone) was the only tweak needed.

Over the past three years I have shown small clips of classroom activities to students, asked them to tell me what they are doing in the video and why, and walked away with both some first class lesson modifications as well as a deeper respect for students’ ability to understand and modulate their own learning. Having student groups set their own time limits before engaging in a task; instituting a 2-minute ‘note-taking-break’ in the middle of activities; creating two ‘solo-corners’ in the room for students who want to work individually; all of these ideas came from students who watched a video of themselves in class and told me what they were doing and why. All of these ideas have helped to make my classroom a better and more comfortable place for learning to happen.

Sometimes I think that becoming a more effective teacher is simply a process of becoming aware of the nearly obvious. At one time in my teaching career, I didn’t realize that oral and written instructions only have meaning if students can understand them or try to do so. I didn’t know that students often want time to correct and rewrite errors in their written work. I had no idea that simply asking a student what another student had just said in class (the old “What does Keisuke think about that” trick) leads to better output and higher rates of attention in class. All of these things seem so obvious to me now, but at one time they were hidden in the blind spot between what I knew about teaching and what I could see happening in my classroom. Taking short videos of my classroom and sitting down with my students helps me shrink that blind spot. It makes the almost obvious, obvious. But just as important, by sharing these videos with my students over the past few years and hearing what they have to say about them, I’ve come to realize that my students care deeply about the quality of their lessons and my development as a teacher. I’ve come to understand that listening to my students helps to make me a better teacher because listening to them and respecting their ideas and experiences is at the very heart of learning itself.

By Angelos Bollas

In the teaching days prior to receiving professional training, not only did I not ask my students for their feedback in regards to my teaching but also did not even think that it could make my lessons better in any way. Thinking back, I can also confess that this did not happen consciously. In other words, I was not uninterested in what they had to say about our lessons; I just didn’t know any better. I am sure there are many teachers out there who are so overwhelmed by the things they have to do in a lesson that they ‘forget’ to ask whether the learners actually learn, enjoy, or want something different from the lesson and/or the teacher.

In this post, I would like to share my experience of making students’ reflection an integral part of the lessons I taught last year at a pre-sessional course offered by a UK institution of higher education to international students who applied for Masters or Doctorate studies. The course, lasting 10 weeks over the summer, focused on the development and honing of students’ academic skills so that they would be able to cope with the demands of their postgraduate course after completing it.

It was their cultural and educational background that made me realize in the beginning of the course that there was a real need for me to see whether my teaching had any effect. By that time, I had experience teaching students from all over Europe and North America but I had never taught students from China, Japan, and Saudi Arabia. Thanks to my previous training, I was aware of the relevant literature that described learners’ academic strengths and weaknesses (in relation to learning English, that is) and I did consult different sources, but I was still not sure that this would be enough. So, the first thing that I introduced was an online learning diary.

Online Learning Diary

I set up a wiki space using PBworks (click here for more information) and had the students create their own private pages. Every Friday they were asked to provide short answers for the following questions:

I really enjoyed reading the students’ responses not only because I could make adjustments to the following week’s planning but also because they were unconsciously practicing their writing skills. However, given the pace of the course, after the first couple of weeks students started seeing this as an extra assignment for which they had no time and, since it was not part of their formal assessment, they were not very keen on completing it. Once I realized that this didn’t work anymore, I thought of using questionnaires at the end of each teaching day; this way, students would not have to do anything other than tick the boxes.

Questionnaires

The questionnaires were very simple in design. Most questions asked the students to choose a yes/no answer and were all followed by a short-answer question. A sample question would look like this:

Did you enjoy today’s class?

Yes No (circle the one that applies)

Why? (answer in a short sentence) _____________________________________________________________

Indeed, students were happier completing such a questionnaire each day rather than having to log into our wiki space, find their page, think of all the tasks/activities we had done each week, and start typing paragraph-long answers. When it comes to the quality of the feedback I received, though, it was significantly lower than the one I received through the online learning diary. Not surprisingly, after 6 hours of lessons, students wanted to complete the questionnaire as soon as possible so that they could leave the lecture hall and go home. It was also a less environmentally friendly solution, so I had to think of something else.

In trying to find a more effective way of collecting feedback, I remembered what I usually say to teachers when they ask me about best tech tools: use the one your learners are most familiar with. The majority of my students were using WeChat, a free messaging app similar to WhatsApp, so I put it to use for getting their feedback.

WeChat for feedback

We set up a class group on WeChat and students were asked to add a short comment after the end of each session (not after the end of each teaching day). This time, there were no pre-assigned questions or any guidelines and the responses I received were similar to these:

“Very difficult text”

“Difficult words”

“Nice game”

“Let’s do this again”

“Can we not read another text about engineering?”

“I like doing exercises in groups”

The most interesting thing about this method of collecting feedback was that I was receiving it after the end of each session, which meant that I could make on the spot changes for the remaining sessions of the day.

In my opinion, all three ways of collecting feedback are very helpful; one needs to find the right one for their own teaching/learning context. For my context, the one that worked the best was using WeChat. It allowed my students to use a platform they were familiar with and were already using anyway, which meant that they did not ‘forget’ to send their feedback. Due to the limited length of their comments, it did not look like extra homework for them and allowed them to be concise.

There are certainly other means for gathering feedback that have not been mentioned in my post, such as Google Forms, Tutorials, and many others. It would be really useful for me and all readers of this blog if you added your thoughts and/or preferred methods for collecting feedback from your students in the comments area below!

By Anne Hendler

By Anne Hendler

When I started teaching, I had never taken any training. I learned on the job, and it was natural that I learned a lot from my students, even the youngest ones.

I have always valued student feedback. After all, they were really the only ones who saw my classes. Maybe they weren’t experts at teaching or learning, but they were (1) the customers and (2) the benefactors of the experience, and they knew what they liked, what made them feel confident or successful, what was fun, and what was boring. They saw things I didn’t. They saw what happens in the classroom in ways that I didn’t.

Initially I received feedback from students informally – by observing them, or by asking them directly in class or in the hallway, or by listening when they approached me individually or in groups to tell me what they thought.

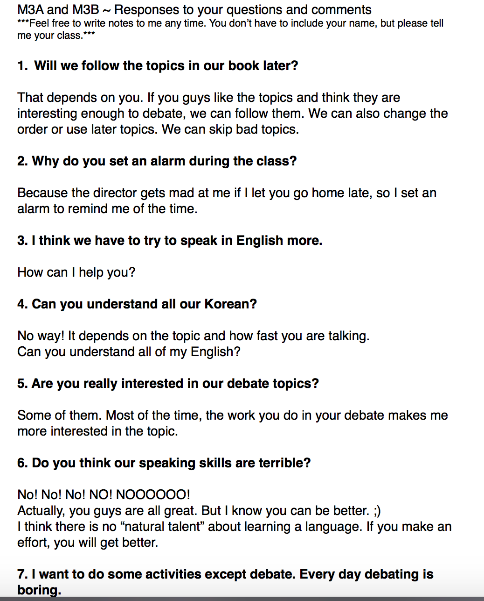

When I started collecting feedback formally (primarily with teens), I passed out surveys, added a question to the end of their exam, facilitated discussions, and did a variety of activities to get them to express their opinions. It was a process – initially they just wrote vague and positive comments, such as “Everything is great.” “We love you.” It took time to build the trust required for more detailed feedback. After a while, they started giving more specific answers: “I want to do more games.” “I think this project improved my English.”

At that point, I realized that I couldn’t just collect feedback. I had to read it and let the students know I was listening to them. I had to answer their questions and respond to their comments. So whenever I collected feedback, I typed it up into a document or spreadsheet and gave it back to them. We spent some time in class talking about it. Something about writing it all up was really helpful to me as well. Here are some things I learned from this process.

The questions they asked, in their turn, truly revealed the things they cared about. The trust we built through such questions and answers helped to open the door for hallway feedback. I’ll never forget the day a student came to me in the hallway at the end of a long day. Her class had been the last of the day and particularly challenging on that day. She said, “we are tired when we come to your class because of the pressures in our day and our other classes. So maybe we look bored, but really we are doing our best. We just need more time.” Her unsolicited feedback helped me to see the class in a different way and reminded me how valuable it is to build a mutual feedback relationship with students. It developed their reflective skills as well as my own, and gave me another lens through which to observe my classes.

Why do we need feedback? Who is it for, teachers or students? What are some of the techniques to provide it? In this issueTheodora Papapanagiotou and our two new bloggers, Zhenya Polosatova and Patrice Palmer, will discuss various ways to look at feedback in teaching and teacher training.

|

|

|

|