Believe in Your Students, not in Myths

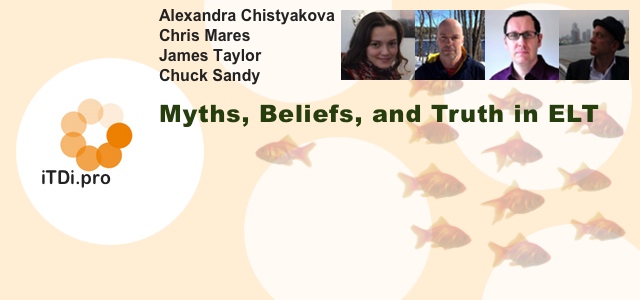

Alexandra Chistyakova

Myths, biases, and misconceptions seem to accompany almost every aspect of human life. Some of them are based on preconceived opinions, some stem from misinformation or distorted facts, while others are formed in a slapdash manner simply out of laziness.

Teaching is no exception to this rule: it is also surrounded with myths and beliefs. As many of us have been through some educational institutions we have some certain ideas and notions of the educational process. Certainly, our ideas are largely based on our own first-hand experience and depending on how successful or not our experience has been, we hold various, sometimes opposing beliefs about teaching and learning. Also, our views depend on the roles we play in the process. As learners, we tend to look at learning, teaching and our teachers, in particular, from one perspective, while, as teachers, we see the other side of the situation. Not surprisingly, learners and teachers’ perspectives do not always match. Rather, far too often, teachers and learners are found on the opposite sides of the barricades.

However, the fact that there are so many various and sometimes contrasting ideas about teaching and learning is only beneficial as it helps all parties involved to reflect on and reconsider their attitudes and practices, thus making education more efficient. However, when some ideas are spread around without decent critical examination, they may turn into myths. This is especially alarming when such myths take root in teachers’ minds and influence teaching practices. That is why, these are teachers who not only can but, in fact, should look at the educational process from all perspectives and try to be open-minded and flexible as possible.

Unfortunately, this is not always the case. Sometimes, teachers are inclined to look at the learning process mostly from a teacher’s standpoint disregarding students’ views and wishes. Such one-sidedness is a trap because it leads to a biased opinion of learners and the teaching profession, in general. In other words, one-sidedness breeds myths.

Among all possible misconceptions and false beliefs teachers might have about learning and learners, there is one I particularly feel strongly about. This is a belief that there is no use worrying too much about what learners take from your lessons because they won’t retain what you taught them anyway.

I remember being told this by one of my colleagues a couple of months ago. I also remember that it made me absolutely stunned and literally speechless. I didn’t know what to say in response, but I immediately knew that this idea was totally wrong.

A teacher is someone who does care. This is someone who is there to help learners to move towards their learning goals and ambitions. And while in teaching, it takes two, the teacher and the learner, to tango, this is the teacher who should outline and create the most favourable conditions for learning to occur and thrive. If learning doesn’t happen, especially consistently, it’s the teacher’s responsibility to stop and reflect on what is not working, what is standing in the way and what should be altered or improved.

If your learners take little if anything from your lessons, is it solely the learners’ fault? Should learners be blamed for the absent-mindedness, lack of motivation and indifference? Are the learners the root of this problem? Unfortunately, some teachers are convinced in this myth.

This is extremely upsetting to see teachers stick to such limiting perception of their learners. Such attitude undermines the very nature of teaching. How can teachers keep on giving and sharing if they do not believe in their learners? How can teachers truly invest in their learners if they depreciate the learners’ potential by default? How can students succeed in learning if teachers themselves do not believe in their success?

Ironically, this myth maintains itself quite easily. Teachers who hold it find the confirmation of it in their everyday practice: they see poor results, they feel discouraged and frustrated, but instead of trying to reflect on the real causes of low grades or mediocre outcomes, teachers put an accusing finger at learners’ unwillingness to learn. This way, the myth is cemented. However, what really happens in such situations is that once teachers lose faith in their students and stop taking care of the learning outcomes, they build up a wall between themselves and their learners. This, in turn, leads to the growing feeling of dissatisfaction and detachment in learners. Thus, there are low grades and slow progress.

To dispel this myth and break the vicious circle of mistrust and poor results, teachers should never lose faith in their learners. Teachers are here to strike a spark and ignite students’ desire for learning. This initial impulse and genuine care are all that is needed to secure successful learning. And trust me, once students are awakened and engaged in learning, they will take care of their learning themselves just fine. This will happen because insatiable curiosity is in the human nature. I strongly believe in this.

Connect with Alexandra and other iTDi Associates, Mentors, and Faculty by joining iTDi Community. Sign Up For A Free iTDi Account to create your profile and get immediate access to our social forums and trial lessons from our English For Teachers and Teacher Development courses.