John F. Fanselow’s work has a continuing influence on generations of teachers, teacher trainers, and material writers. This year marks the 25th anniversary of his ground-breaking book, Breaking Rules. What better time to join John on a journey of discovery in an intimate five-week online course designed by John to help teachers make real changes in their teaching as they learn to see the obvious, break unconscious rules, and try the opposite? Click for further course details and registration here.

What Would Happen If …. ? John F. Fanselow

Sit down before what you see and hear like a little child, and be prepared to give up every preconceived notion, follow humbly wherever and to whatever abyss Nature leads, or you shall learn nothing. — T.H. Huxley

The most frequent questions I am asked after workshops and classes are usually about how I come up with activities and why I insist on making even my plenary sessions interactive. My short answer usually is, “I have no idea.” I do offer possible explanations but always with the caveat that explaining why we do and do not do things is very, very, very speculative.

I do not advocate breaking rules to be different or distinctive but rather to explore.

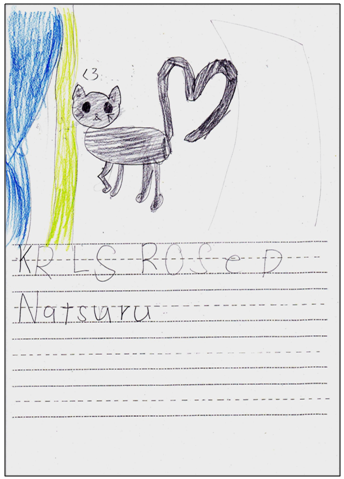

The first candidate is the curiosity we are born with. I tap this and so I consider what I do as natural and perhaps quite normal. For me, breaking rules and doing the opposite are simply attempts to answer the question we ask as children,

“What would happen if . . .?”

Like a child, I wonder.

As a child, I was curious about how switches turned lights on and off, partly because my father was an electrician. My father gave me switches to play with, which nourished my curiosity.

I was curious about more than switches. My parents bought me a chemistry set and an erector set, which had motors and metal parts, I could screw together to make things like windmills and bridges. I learned knot tying, canoeing, plant identification in the Boy Scouts. I built a clubhouse in our yard from lumber my friends and I scavenged along the railroad tracks near our house.

In addition to these activities that were at that time reserved mainly for boys, I also became interested in baking. I loved desserts and wanted to learn how to make them. I learned by watching a TV show. I was the only boy in our neighborhood that was making éclairs, angel food cake and fruitcakes, to name a few desserts that particularly fascinated me. My classmates were playing baseball and other sports as I was baking. My parents were very indulgent and let me follow my curiosity wherever it went rather than stifle it.

As I said, reasons why I continue to want to always ask, “What would happen if . . .?” is speculative. But I want to state some ways that people misunderstand Breaking Rules that are not speculative but true.

First, I do not advocate breaking rules to be different or distinctive but rather to explore. The subtitle of my book Breaking Rules is Generating and Exploring Alternatives. I urge teachers to try alternatives to see what difference they make. If we do the same thing over and over not only are we likely to be bored, but our students will be also. Vitality comes from change. Routine leads to stagnation.

Second, I urge teachers to analyze what they do rather than to judge what they do. Judgments, based on preconceived notions and beliefs, prevent genuine exploration. “I can’t do this because my students will be confused,” we might be tempted to say, but we can only see to what extent our students will or will not be confused if we try the this. We have to also ask how being confused could possibly be positive rather than negative.

Third, I urge teachers to describe in very, very precise detail what the words It works and It doesn’t work refer to. Hardly any teachers record and transcribe parts of classes to identify the It much less the works and doesn’t work. When teachers analyze transcripts of their teaching, they can see that the claims we usually make for what works and does not work are so general as to be meaningless. There are loads of other terms that are equally dangerous such as scaffolding, positive feedback, lived experience. These are not only imprecise but inconsistently used so if we look at five teachers saying they are doing scaffolding, we will see that they are doing five totally different activities.

Fourth, I advocate that teachers see that any communication has multiple characteristics. In Breaking Rules I identified 5—the source and target, the purpose, the medium used, the way the medium was used and the content. Each person can add others or create their own, but we cannot describe any communication with only one label.

We need to look at what we do, make small changes, and compare the results.

A fifth theme of Breaking Rules is that very small changes—asking students to underline words they know rather than ones they do not know—can have very large consequences. Such small details are rarely noticed much less discussed in post observation conversations or articles about methods. Again, the point is precision, not breaking rules to be rebellious or different.

Finally, I advocate that teachers make multiple interpretations of transcriptions of what they and their students say and do. Did the students learn anything? Did they enjoy it? Was their curiosity nourished or dampened? Did they become more able to learn on their own? The words I just used are fuzzy and slippery which is all the more reason to discuss multiple interpretations with many examples and always asking how what we think is good is not and how what we think is bad not.

I just said “Finally” but I lied! The central point of Breaking Rules is that I believe that we should not listen to so called experts, researchers or leaders in our field alone. Rather, we need to look at what we do, make small changes, and compare the results. Of course we can learn a lot from reading and attending conferences. But we can learn much more and can be more powerful teachers if we explore what we are doing in precise detail.

He who would do good to another, must do it in Minute Particulars

General Good is the plea of the scoundrel hypocrite & flatterer:

For Art & Science cannot exist but in minutely organized Particulars

– William Blake, quoted in Breaking Rules.