Thinking Is Critical — Barbara Hoskins Sakamoto

Course Director

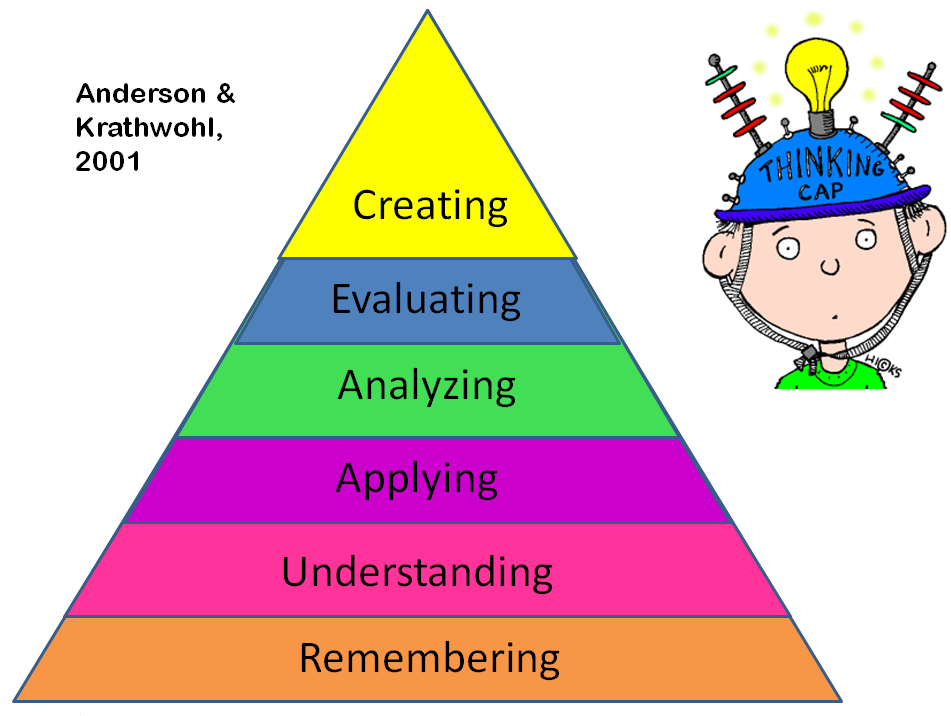

Long, long ago, when I was working toward my first teaching license, I was introduced to Benjamin Bloom and began a love-hate relationship with his taxonomy of learning objectives.

I loved having a rubric that helped me include higher level thinking skills in my lessons. I hated that my lessons so rarely touched on the skills at the top of the pyramid. It’s easy enough to write lesson objectives that incorporate higher order skills:

Students will analyze the appeals used in popular television advertisements, evaluate which appeals were most effective, and create an original advertisement incorporating one appeal from each of the categories studied.

The challenge is to make sure that students remember the names of the persuasive appeals, understand how they are used in advertising, and can apply that knowledge in new contexts so that they can make the most of the more challenging tasks. It’s the time spent on building the lower level thinking skills that make the class project a meaningful activity.

If we’re doing this activity in a language class, we also need to make sure that students are comfortable with the language needed to discuss, negotiate, and produce a group project. The tasks at the top of the thinking pyramid reinforce the language and concepts that we’re trying to teach. But, without the foundation of remembering, understanding, and applying language, students will be unable to accomplish the tasks in English. On the other hand, teaching language without also teaching students to think when using it can produce students who answer questions with grammatically correct utterances that make no sense in context. Naomi Epstein addresses this problem, and introduces a simple approach that helps students become better at producing answers that are relevant to the type of questions being asked in her The “Reading Pictures” Strategy.

All levels of thinking are critical. And all have an important place in our classrooms.

I like the visual image of a pyramid because it helps me remember that my goal in teaching English is to make language a tool that has value in my students’ lives outside of class. For that to happen, I need to help them make connections between the language they’re learning and the creative ways in which the language can be used. One cannot happen without the other. In Moving beyond “Do you like? Randy Poehlman shares a clear step-by-step example of how he builds the language students need to discuss, share, and support opinions.

The taxonomy can be a useful tool for incorporating higher order thinking skills with even the youngest learners. For example, rather than telling your students why we say It’s a ball but It’s an apple, give them several examples and let them figure out the rule behind the pattern. Even if your students don’t have the language to explain to you that whether to use a and an depends on the initial sound of the word following the determiner, they can show you that they’ve analyzed the language by providing the appropriate determiner in front of new words.

Games like I Spy or Twenty Questions encourage problem solving as students learn to ask smarter questions without feeling like hard work. You can also challenge your students to solve a problem that you face in every class, coming up with activities that practice target language in an enjoyable way. Rather than choosing a project or creating a game that reinforces language objectives, let your students come up with their own solution. The process of creating a game, of coming up with and testing different rules for play, and then evaluating how well the game meets the language objective is an easy way to strengthen your students’ thinking skills while using language for a real purpose.

We do something similar in our English for Teachers course by asking teachers to focus on both language and teaching objectives in our lessons. For example, in EFT Lesson 2, teachers strengthen their language skills by focusing on collocations and logical connectors in listening, vocabulary, grammar, and reading sections. Not too different from any language course, except that the context for lesson is teaching – in the case of EFT 2, about how we can incorporate a variety of thinking skills in our lessons. (We made sure that the language focus was authentic and relevant by having discussions on the same topic with our iTDi Associates first, and pulling language for the lesson from those conversations.)Teachers connect the language they’re learning to their own experience by participating in discussions about teaching thinking skills with iTDi Mentors and other teachers working on the same lesson.

Thinking skills and language skills are not separate learning objectives. Including both in a lesson creates a more effective learning experience. The key, I think, is to find what motivates your students – games, projects, discussions, or something else – and use that to engage them in lessons that build both their language and thinking skills.

~ Barb

Connect with our iTDi Associates, Mentors, and Faculty by joining the iTDi Community. Sign Up For A Free iTDi Account to create your profile and get immediate access to our social forums and trial lessons from our English For Teachers and Teacher Development courses.

Rules I Follow

Rules I Follow