The Technology of Self-discovery and Self-expression

Many teachers believe that technology is the thing you have to bring into your classroom to make your lessons more interesting. I don’t share this belief. I believe that the only thing that makes a class interesting is relevance. Context and purpose are the determining factors: not interesting websites, cool apps or funny videos.

I don’t use technology in my classes. I use it to prepare for and to follow-up on what happens in my classes. Technology is in the classroom for the students to use. My job is to create meaningful lessons for my students so that they can use it when they think it’s relevant.

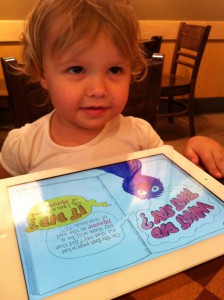

Children today from the age of 2 onwards have their own taste in the kind of technology that helps them express themselves. Sophie, my two-and-a-half-year-old daughter, has definite tastes in the kind of content she enjoys. She has about 50 different apps and books on her iPad but she consistently chooses the five or six that she finds attractive. She enjoys using those and they open up directions for her own inquiry. She doesn’t need clever Daddy to tell her which apps to use. She makes her own decisions and those decisions will lead on to new ones, different ones, and perhaps even better ones.

I love technology and consider myself really lucky to live, teach and have children in an age when we have almost complete freedom of learning and information. Being able to share all this learning and information is exhilarating: not because of the technology itself, but because of the freedom it provides, which includes the freedom of choosing not to live with it.

Why would I, as a teacher, try to impose specific types of technology – however ingenious – on my students!? I believe that my job as a teacher is to let my students explore and experiment with whatever technology helps them learn and express themselves. When I use the word technology, I mean it in the widest possible sense.

It can be a pen and paper. It can be a word processing programme. It can be a computer game or a social media platform. I will always be as happy to give feedback on a piece of writing written on a piece of paper torn out of a Maths exercise book as I am when given a blog post or a video to comment on.

The only reason I have technology in my classrooms is to provide students with new opportunities of self-discovery and self-expression. Technology is an amazing tool that helps people learn about things they have never before encountered and become interested in things they didn’t previously consider interesting. One of the most uplifting things that can happen in a classroom is when a student you don’t feel you are reaching tells you about or shows you something they’ve done that blows your socks off.

I once gave my grade 11 students a topic, and asked them to write a blog post or a composition about it. Two boys in the class decided to make a video instead. They spent weeks preparing it, and put more work into making that two-minute video than everything else they had done for the whole year. Was it a good video? Honestly, no, not really. Does it matter that it wasn’t? No it doesn’t matter at all. Did they learn anything in the process of creating the video? OH, YES.

Was it English? Well, there was that of course, but there was also so much else they learnt that I couldn’t help but feel very, very proud of them and of myself. The pride in their eyes when they presented their video was enough to blow my socks off and shut up the other cynical 17-18-year-olds in the classroom. For me, that’s what technology is all about.