Project-based Learning for Teaching Language

Malu Sciamarelli

Introduction

Introduction

Successful language learning can be achieved when students have the opportunity to receive instruction, and at the same time experience real-life situations in which they can acquire the language. In my opinion, there is no better way of doing so than by using projects in the classroom.

Project-based learning has been widely known and used in the teaching of subjects such as science, geography, history, and also in arts and languages for many years. But what is project-based learning, or simply PBL? PBL is a classroom approach in which students explore real-world problems and challenges and acquire a deeper knowledge. It is “not a replacement for other teaching methods, but an approach to learning which complements mainstream methods and which can be used with almost all levels, ages and abilities of students” (Haines, 1989).

Characteristics

PBL has been described by a number of language educators, who have approached PBL from different perspectives, but who have shared some common features:

- PBL focuses on content learning rather than on specific language targets. Real-world subject matter and topics of interest to students can become central to projects.

- PBL is student-centered, though the teacher plays a major role in offering support and guidance throughout the process.

- PBL is cooperative rather than competitive. Students can work on their own, in small groups, or as a class to complete a project, sharing resources, ideas, and expertise along the way.

- PBL leads to authentic integration of skills and processing of information from varied sources, mirroring real-life tasks.

- PBL culminates in an end product that can be shared with others, giving the project a real purpose. However, the value of the project lies not only in the final product, but also in the process of working toward the end point. So, PBL has both a process and product orientation, and provides students with opportunities to focus on fluency and accuracy at different project-work stages.

- PBL is potentially motivating, stimulating, empowering, and challenging. It usually results in building students’ confidence, self-esteem, and autonomy as well as improving students’ language skills, content learning, and cognitive abilities.

In addition to it all, from my point of view, a project must be meaningful. First, students must see the work as personally meaningful, as a task that matters and that they want to do well. Second, a meaningful project must fulfill an education aim.

Practical Ideas

This is an example of the project I did with my students, from young learners to adults, which follows all the features of PBL and it is meaningful in both ways.

Quick Recipe Challenge

In class, I gave them strips of paper with the following questions to be discussed:

- What can you cook?

- What do you like to eat when you are really hungry?

- Do you take photos of food at restaurants and post on Facebook?

- Do you have a lot of cookbooks at home?

- What was your favourite food when you were a child?

- Who does the most cooking in your family?

- Can you cook fast under pressure?

- What would be the best dessert for you?

- What do you like to drink with a special dinner?

The time you allow for this discussion depends on the number of students you have in the group.

After discussing all the questions, the students received the instructions and a booklet with recipes that should be studied before going to the kitchen:

You have 15 minutes. Within this time, you and your friends will have to:

- Follow the recipe and prepare the assigned dish.

- Divide the dish into a specific number of smaller portions. They have to be appealing to the eyes as well. Place them in designated “presentation trays”.

- Wash all used utensils. Clear the table and leave the space ready for the following team to use.

After preparing all the recipes, the groups that participated in the project were allowed to eat all the dishes that were prepared!

In the following class, more tasks were assigned:

- for groups of young learners: the teacher mimed some actions that were done in the kitchen, and students had to guess;

- for groups of teenagers / adults: they had to remember five verbs that were used when cooking; a greater challenge would be remember one complete recipe.

Other practical ideas of projects can be found here:

The Kindness Project: http://www.malusciamarelli.com/guest-posts/the-kindness-project-in-the-english-classroom/

Wishes on a Coffee Cup:

http://www.malusciamarelli.com/posts/wishes-on-a-coffee-cup/

Mascot-inspired Projects:

This is a workshop to be presented at JALT Conference in November 2014 (http://jalt.org/conference) with Barbara Hoskins Sakamoto and Juan Alberto Uribe. In this workshop we will share mascot-inspired projects from English classes around the world and show how their inclusion increased motivation and engagement for students. We will document the workshop on a wiki to serve as a resource for participants and teachers who are unable to join.

Benefits of PBL

Research shows that compared with students receiving traditional instructions, those participating in PBL:

- become more engaged, self-directed learners;

- learn more deeply and transfer their learning to new situations;

- improve problem-solving and collaboration skills; and

- perform as well or better on high-stakes tests.

(Barron & Darling-Hammond, 2008; Brush & Saye, 2008; Strobel & van Barneveld, 2009; Walker & Leary, 2009).

Conclusion

PBL is an exciting way of teaching. It is a way to reach all students and get them engaged; give them ownership of their learning and make them lifelong learners; give them critical thinking and problem-solving skills that they need as soon as they walk out of the classroom into the real world.

References

Haines, S. (1989). Projects for the EFL classroom: Resource material for teachers. Walton-on-Thames Surrey, UK: Nelson.

Henry, J. (1994). Teaching through projects. London: Kogan Page Limited.

Legutke, M. & Thomas, H. (1991). Process and experience in the language classroom. New York: Longman.

Richards, J. & Stebbins, L. (2013). Current Research on Project Based Learning. In Research Supporting the Design of WIN Math and WIN ELA. Available online at: http://www.winlearning.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/WINProjectBasedLearningV2.pdf

Connect with authors, iTDi Associates, Mentors, and Faculty by joining iTDi Community. Sign Up For A Free iTDi Account to create your profile and get immediate access to our social forums and trial lessons from our English For Teachers and Teacher Development courses.

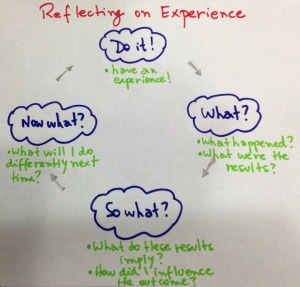

At the end of each class, I and the students always reflect using the Reflective Learning Cycle (Thornbury S. and Watkins P.), in which they can see their learning in a motivational, personal and meaningful way.

At the end of each class, I and the students always reflect using the Reflective Learning Cycle (Thornbury S. and Watkins P.), in which they can see their learning in a motivational, personal and meaningful way.