A Reminder that Learning is Learning

A Reminder that Learning is Learning

by Kevin Stein.

I have been a teacher for twenty years. Over that time, I have often been given a list of program goals at the beginning of the school year. The goals are often things like an expected average increase in students’ standardized test scores, minimum acceptable results for student and parent satisfaction surveys, and class attendance rates. When I first started, I would sometimes see what was happening in my class through the lens of these goals. If a class did not go particularly well, if students wandered off task during a speaking activity, or if there were a bunch of frowning students shuffling out of the classroom at the end of a lesson, I would feel a little flutter of panic. Would my bosses think I was failing at my job? What was going to happen at the end of the year when my students all checked off boxes that stated I was a barely satisfactory teacher?

As I got used to teaching, I became much more focused on what the students were actually learning in my classes and spent less and less time thinking about those program goals. I was lucky enough to work with a team of teachers who wanted to share their own teaching experiences and did not hesitate to honestly tell me how those experiences did or did not help learning take place in their classrooms. We were, as a team, also lucky enough to work with my mentor and friend, John Fanselow. John constantly pushed us to pay close attention to what our students were doing in class and to compare and contrast the impact on learning of small changes we could make in our classroom. We all tried out simple changes, such as where we stood during an activity, or how long we waited for a student to respond after asking a question. And as we all became more adept at noticing how and when learning was taking place, students began to reach those goals which, for the most part, we no longer thought about on a daily basis.

As we worked together and worked with John, we came up with a list of ideas that we still have hanging on the wall of our staff room. These are our beliefs about what we are trying to do as teachers, the principles born out of our shared experience:

- Students know how to learn. They have been learning and succeeding at new things their whole lives. Our job is to remind them of this simple and amazing fact.

- When students are learning something new, it is not our job to replace that process of discovery by telling them what and how to learn, but to make the process as smooth as possible.

- Students learn best when they have a chance to see and hear HOW they are learning. When students are engaged in an activity, they are often wholly focused on completing the activity. Providing students with time to watch and listen to videos or recordings of themselves in the process of learning helps them to see how some of the things they do are effective and some are not.

- When provided with multiple examples of language in context coupled with enough time, students can and will (with occasional hints) notice features of that language which they want to use.

- Students who come to school are all motivated! If they really did not want to learn, they would find a way to avoid your class. So treat the students with the respect they deserve for wanting to learn.

- True goals are internally generated. Regardless of suggestions we make as teachers about what kind of score we think a student should get, or what kind of language a student should be able to use, it is the students themselves who decide what they want to accomplish. We need to help students articulate and reach those internal goals.

- Students have a rich and important life outside of our classrooms. When they make a decision to prioritize one aspect of their life over our classes, we should treat that decision with, at the very least, respect, and if possible help a student tie those other experiences to their learning goals.

- Acquiring a language is a wholly personal endeavor. We might have 10 or 20 or 30 students in our classroom, but each of those students experiences class as an individual. Our job as teachers is to create an environment where there is enough emotional and cognitive room for each student to truly participate in their OWN class.

When I became a manager three years ago, program goals, some of which I was asked to create myself, suddenly began to once again seem like the most important part of my job. I began to keep myself up at night worrying about how far behind we were in the race to reach those numbers that stretched out like a ribbon across the finish line of a100-meter dash. I would observe a teacher’s lesson and count frowning faces and empty chairs. I would nervously open emails from TOEIC or download the test results from the EIKEN site. I was miserable. I’m pretty sure I was making the teachers miserable as well. And all because I had somehow convinced myself that I was indeed in a race, a sprint to reach a set of numbers I had long ago realized were the result of an effective program and not truly the goal of teaching.

At the beginning of this academic year, I took another hard and long look at that list of beliefs and principles of what it means to be a teacher. And I realized that whether I am a teacher or a manager, my job is to help learning take place. The beliefs and principles upon which I had done my job for the past seventeen years had not changed, even if my title had. While some of the words needed changing, the spirit of what was being expressed did not need to change at all:

- Teachers have a rich and important life outside of their jobs. When they make a decision to prioritize one aspect of their life over their work, we should treat that decision with, at the very least, respect, and if possible help our teachers tie those other experiences to their professional goals.

- Acquiring the skills to be a teacher is a wholly personal endeavor. We might have 2 or 5 or 20 teachers working in our school, but each of those teachers experiences the process of becoming a teacher as an individual. Our job as managers is to create an environment where there is enough emotional and cognitive room for each teacher to truly become themselves as teachers.

- When provided with multiple examples of learning happening in context coupled with enough time, teachers can and will (with occasional hints), notice features of how that learning was fostered, which they might want to use in their own practices.

- True goals are internally generated. Regardless of suggestions we make as managers, it is the teachers themselves who decide what they want to accomplish. We need to help teachers articulate and reach those goals.

- Teachers who come to work are all motivated! If they really did not want to teach, they would have chosen a different (and higher paying) profession. So treat the teachers with the respect they deserve for becoming a teacher.

- Teachers learn about teaching best when they have a chance to see and hear HOW they are teaching. Providing teachers with time to watch and listen to videos or recordings of themselves in the process of learning helps them to see how some of the things they do are effective and some are not.

- When teachers are learning something new about teaching, it is not our job to replace that process of discovery by telling them what and how to teach, but to make the process as smooth as possible.

Perhaps most importantly of all, I realized that being a manager is not about facilitating some kind of race. Becoming a teacher is not a sprint. There are no trophies, no gold medals waiting just beyond the finish line. It is a long and often difficult journey taken one step at a time. The best we can do as managers is to support and walk with our teachers whenever possible, and to help them see, with both patience and humility, that all teachers know how to learn. They have been learning and succeeding at new things their whole lives. A manager’s joy is to remind teachers of this simple and amazing fact.

[I would like to thank John Fanselow for all the support he has showed me and the program at my school over the years. Many of the ideas touched on in this article can be found in John’s writing and are also a direct result of his advice and input. I would especially like to recommend his new book, Small Changes in Teaching, BIG RESULTS IN LEARNING. It is full of insights that can help teachers both recognize and foster learning in all of their classes. It is also a book full of the warmth and spirit that I hope to bring to my classes and school.]

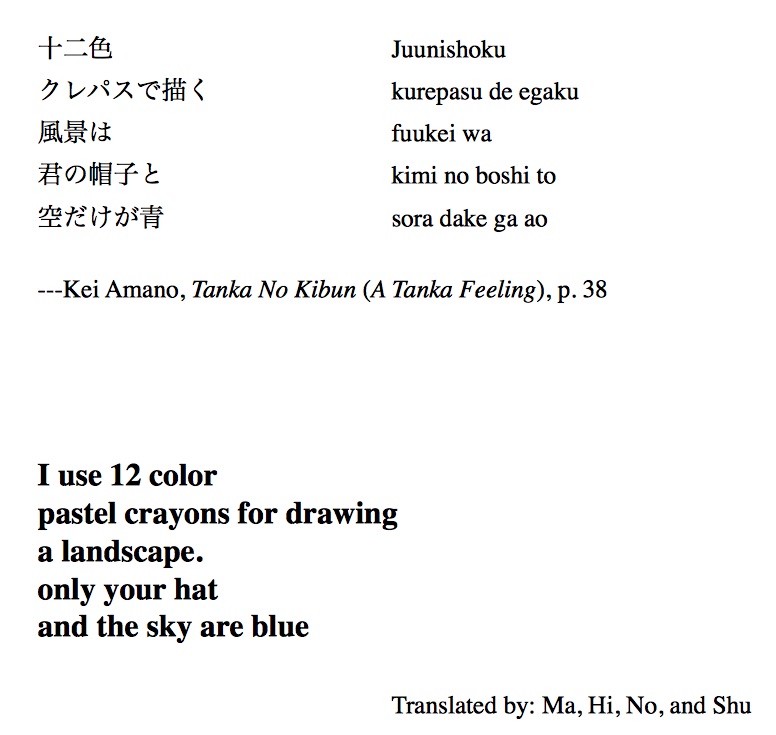

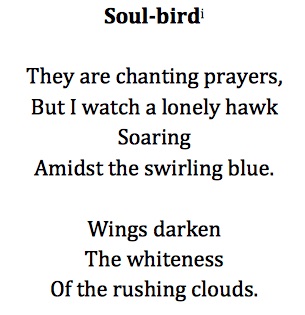

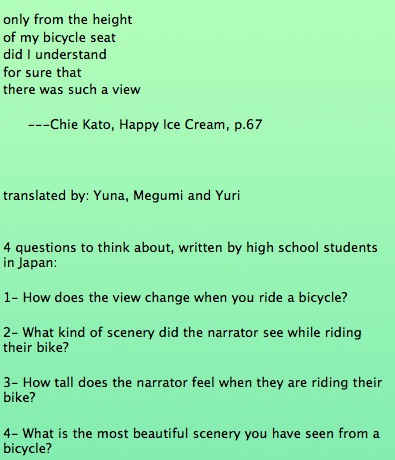

[This post is dedicated to the students in the Bachelor of Social Work programme at Martin Luther Christian University in Meghalaya, India who inspired my students to think deeper, ask questions, and search for the personal meaning in the poetry around them.]

[This post is dedicated to the students in the Bachelor of Social Work programme at Martin Luther Christian University in Meghalaya, India who inspired my students to think deeper, ask questions, and search for the personal meaning in the poetry around them.]