Sandals? You’re kidding.

I wore shoes till I lived in Nigeria. When I got athlete’s foot during hot and humid summers in Chicago, I bought off the counter ointments and they relieved the symptoms somewhat.

In Nigeria the temperature and the humidity were much higher than those I had experienced in Chicago. The off the counter ointments had very little effect.

So I went to a doctor and asked for a prescription ointment. He said there was no need for ointment. All I had to do was wear sandals. Well as I said, I had worn shoes all my life and I thought of all sorts of reasons why sandals would not be a good option. They would not support my arches well, my feet would get dirty from the dust in the places where I walked, insects would bite my toes, they seemed too casual to wear with the shirt and tie that I wore when teaching, and people would smell the odor from my feet.

The doctor refused to prescribe ointments and insisted I try his suggested alternative. So I bought a pair of sandals. None of my fears materialized.

My feet had no odors, the small amount of dust that accumulated I could shake off in a heartbeat on my doorstep. The sandals I bought had strong arch support. My students said they thought that sandals were more stylish with shorts in the tropical rainforest. They said they had thought it strange for me to wear shoes.

I continued to wear sandals after I returned to New York because my feet continued to be so healthy. When I went to buy a new pair, my wife, who is Japanese, was with me. The salesperson asked me whether I ever visited Japan. I said I often did. He said that he would like me to try on a pair of sandals without straps. He knew that the Japanese remove their shoes before entering their homes. “You won’t have to bend over or sit down each time you enter and leave to strap and unstrap your sandals with these with no straps.”

I said that the sandals would fall off. He said they would not. I said that when I drive they will not stick to my right foot and, as a result, I will not be able to brake quickly. He kept saying that there is no difference between sandals with and without straps as far as keeping them on goes. I said I found this hard to believe.

He got up abruptly and returned with a pair of sandals without straps. He gently removed my sandals with straps and put the sandals without straps on. He said, “Please walk.”

I walked. They did not fall off. They were just as secure and comfortable as those with straps.

Skepticism

We are all creatures of habit both inside and outside of our classrooms. We follow rules that we have unconsciously learned. We get used to doing things in a particular way that we feel comfortable with.

One result of this fact is that, just as I first resisted sandals and then sandals without straps, when people suggest alternative activities for our teaching we conjure up all sorts of reasons why the alternative activities will not work. When we feel comfortable doing what we do, we continue acting the same way.

My suggestion is for you to be as skeptical about your present practices as about the alternatives. Ask how widely advocated pre-reading activities (such as brainstorming, scaffolding, predicting what a text is about) might not only be useless but also detrimental to learning. Question the value of memorizing individual words on note cards with the first language equivalent on the back of the cards. Consider ways that asking students to define words, or use new words in sentences, repeating words in isolation, memorizing rules in either English or students’ first languages, having students in pairs talk about their favorite songs, sports or whatever might be detrimental.

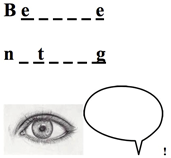

A singular message

I have never seen anyone else share this message at the beginning of each class or at the beginning of workshops or presentations that teacher educators make:

But if I am true to the question I started with, ? vrthng, then you must not only not believe anything I say but anything anyone else says. Do one of your usual activities, make a small change, and compare the effects, over and over and over.

If you follow these steps you will see how much more both you and your students are capable of. You will discover that inertia can be overcome with often exhilarating effects.

The changes I suggest are small, just as changes from shoes to sandals with straps to sandals without straps are small. But the results can be very big. The changes are also easy to employ, just as changing what we wear on our feet is very easy to do.

The three biggest issues in ELT

For me, the lack of skepticism, which I just mentioned, the acceptance of prescriptions and labels is the first one of the three biggest issues in ELT. The second is our failure to analyze what we and our students actually do. All too often we discuss what we do and plan lessons using labels with positive connotations: pre-reading activities, scaffolding, positive feedback, pair work, communicative activities, re-casting, comprehension check, activation of prior knowledge, experiential learning to name ten of dozens. We use the terms the same way doctors use low density and high-density cholesterol and vitamin B12. But the terms in our field are very, very imprecise. Yet we use them to say what we do rather than record and transcribe what we do.

The third issue is the belief that doing A results in B. “Pick a few key words from the text – 7-10 is usually a good number. Have the students write a brief story using each word. This familiarizes students with the vocabulary used in the text. Not only will this help improve reading comprehension, it will improve writing skills as well.” How can the so-called key words familiarize students with the text since they have not seen the text? How can writing a story using each word, many of which they probably are not familiar with, improve their writing? Writing is not using unfamiliar words to write a story with no purpose, no audience, and no theme.

Forget terms. Forget claims about using keywords in stories to improve reading comprehension and writing. Let’s look at the reality of what we do by analyzing recordings and 20 to 30 transcribed lines of what we and our students do. Describe what was said and done by each participant without using one label. Change what is said and done a little, record and transcribe the small changes and compare the results. Over and over and over. Describe and analyze what you do without jargon and with as few preconceived notions as possible.

In our analysis we have to be skeptical — the first issue — how is what we think is useful not useful and how is what we think is not useful possibly useful? What do our students think about what we do?

I am advocating nothing more than what explorers have urged for centuries:

“Sit down before what you see and hear like a little child, and be prepared to give up every preconceived notion, follow humbly wherever and to whatever abyss Nature leads, or you shall learn nothing”. T. Huxley

More of John’s explorations are coming early 2017 in a new book Small Changes in Teaching Big Results in Learning.