Community Director

On Creating Change

(With A Little Help From My Friends)

– Chuck Sandy

We all want to change the world, but when you talk about destruction, don’t you know that you can count me out. – Lennon / McCartney

When I was six, my kindergarten teacher, Mrs. Spenser, passed out a farmyard worksheet and told us to color the barn, red, the donkey, grey, and the chickens, white. I had no problem with the grey donkey, but why a red barn and white chickens I asked? Mrs. Spenser explained those were the rules and everybody, including me, had to follow them.

I thought about this, and then colored my barn black and my chickens brown — not realizing as I did that I was committing a revolutionary act that would result in my mother being called. When Mrs. Spenser explained to my mom that she could not tolerate rule-breakers, my mother said, “Well, we live across from a black barn and we have a brown chicken. What would happen if you tried to understand that?” Then she hung up the phone. My mother became my hero.

A rule breaking, activist, change-maker is not a rabble-rouser

Activism came next. Having to sit in assigned cafeteria seats seemed like a rule worth fighting, so I got lots of kids to sign a petition and then got everyone loudly chanting “No more assigned seats!” This resulted in Mr. Anderson, the school principal, changing the rule. I won! From that day on, we could sit anywhere in the cafeteria we wanted. I basked in my hero status for a few moments, until Mr. Anderson told me I was now cafeteria monitor, responsible for making sure everyone kept the cafeteria clean and our voices down. He tried to make it sound like an attractive job, but I knew I’d won the battle but not the war.

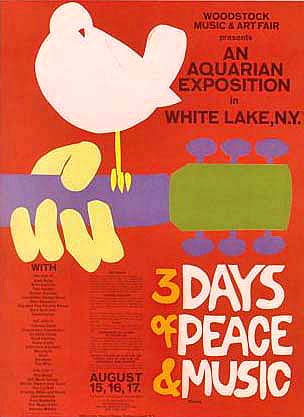

Out in the world a war was happening far away in Vietnam, but TV news brought it home every day. I was 11. Woodstock happened, and Country Joe led 300,000 people in the Fish Cheer and a rousing antiwar song. When I brought that experience to my school’s playground by climbing the jungle gym and leading my classmates in the Fish Cheer, teachers panicked and pulled me down. Later, the principal called me a rabble-rouser and sent me home. At home, my mom handed me a dictionary and asked me to look up the word:

rabble-rouser NOUN (plural rabble-rousers) A person who tries to stir up masses of people for political action by appealing to their emotions rather than their reason. A demagogue.

This was not what I wanted to be. In fact, as a kid I had no idea who I wanted to be, what I was doing, or why. Now, however, as a man in his 50s, I clearly see how these early experiences shaped me and how they eventually lead me to read Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of Freedom, Mark A. Clarke’s A Place to Stand, and John F. Fanselow’s Breaking Rules as I made my way through the years to become who I am: a teacher working for positive change by exploring possibilities within communities.

While there are certainly rules that need to be broken and problems in our schools and society that need to be changed, we cannot go around rabble-rousing and expect to create change by, in Friere’s words, “causing the alienation or demoralization of anyone.” Change becomes possible when we consciously break a rule in Fanselow’s exploratory spirit of wondering what would happen if we do, and then comparing results, or in Clarke’s sense of wanting to “create disturbances that wobble the system” enough to get everyone talking.

Consciously breaking a classroom or school rule to explore what happens and actively wobbling the educational system enough to encourage discussion are positive acts that can lead in hopeful directions. On the other hand, noisily refusing to follow rules, going off on one’s own, or leading a rabble-rousing revolt often just scares people and sometimes leads to the alienation and demoralization of everyone involved.

While we cannot force change, Clarke points out that as teachers we can “manipulate variables in the learning environment and observe the consequences of these manipulations.” Fanselow says essentially the same thing when he encourages us to make very small changes in our classrooms, compare results, and act accordingly based on the reality of what’s going on rather than on some preconceived notion of what learning is and how a teacher should be or behave: not to be different or distinctive, Fanselow wisely points out, but to explore.

When you break a rule or wobble a system, make sure you’re smiling … and that everyone’s eyes are shining.

I believe we can and should be doing exactly the same thing in our classrooms, school systems and educational organizations, and it’s here that I’d like to add something else I learned from John F. Fanselow: When you break a rule or wobble a system, make sure you’re smiling and that in Benjamin Zander’s words, everyone’s eyes are shining.

At this point in my life, I’ve learned to stand in front of a class or a group of teachers and say with a laugh, “well that didn’t work out like I thought it would. Let’s try this instead” or “does anyone have any ideas about how this could work.” Then, just as importantly, I’ve also learned to step back far enough to let others shine as they show everyone a way forward. I’ve also learned that by doing this, my own eyes shine brighter, too.

The key to lasting change is the release of joy and possibility.

The key to lasting change in education is not just rule breaking and system wobbling. The key to lasting change in education is the release of joy and possibility that comes when we work collaboratively in community to change ourselves and cause positive ripples in the world around us. So break some rules, wobble some systems, but do it with a smile. Just keep at it and by all means, don’t worry that you might sing out of tune. That’s fine as long as everyone’s eyes are shining and you have more than a little help from your friends.

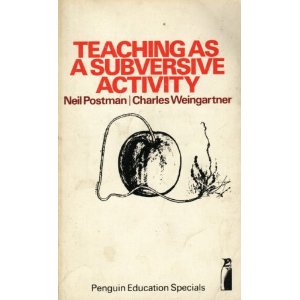

When Neil Postman and Charles Weingartner wrote Teaching As A Subversive Activity in 1969, it was news. It still is. This book is as valid an attack on lock-step teaching and unimaginative schooling now as it was when they first declared that, “There are trivial ways of studying language which have no connection with life, and these we need to clear out of our schools.”

When Neil Postman and Charles Weingartner wrote Teaching As A Subversive Activity in 1969, it was news. It still is. This book is as valid an attack on lock-step teaching and unimaginative schooling now as it was when they first declared that, “There are trivial ways of studying language which have no connection with life, and these we need to clear out of our schools.” Roger’s beautiful book opens with these words

Roger’s beautiful book opens with these words Like many teachers, you might be experimenting with non-traditional ways of teaching. In Clarke’s words you’re “a change agent” promoting not just change in your learners as you create conditions that make autonomous learning more likely. You’re also promoting change in the way things are done. Fantastic!

Like many teachers, you might be experimenting with non-traditional ways of teaching. In Clarke’s words you’re “a change agent” promoting not just change in your learners as you create conditions that make autonomous learning more likely. You’re also promoting change in the way things are done. Fantastic! I’ll let Holt speak for himself, but as you read, replace the word children with the word teachers and the word learning with teaching. Watch what happens.

I’ll let Holt speak for himself, but as you read, replace the word children with the word teachers and the word learning with teaching. Watch what happens. Twenty-five years ago, this book set me free to become the autonomous learner/teacher I’m still becoming. It helped me see what was really happening in my classes, while also giving me permission to explore alternatives. John’s premise is that, “Only by engaging in the generation and exploration of alternatives will we be able to see. And then we will see that we must continue to look.”

Twenty-five years ago, this book set me free to become the autonomous learner/teacher I’m still becoming. It helped me see what was really happening in my classes, while also giving me permission to explore alternatives. John’s premise is that, “Only by engaging in the generation and exploration of alternatives will we be able to see. And then we will see that we must continue to look.”