EFT Course Director

Focus on Creating, Understanding, Sharing

– Barbara Hoskins Sakamoto

If you want to learn how to effectively break rules in young learner classes, look to the experts. If one of the aims of early childhood education is to teach what rules are and why we need follow them, then young learners are experts in the art of breaking them.

We can learn a lot about shaking up the rules we apply to own teaching by watching the way our students approach life and learning. Here are a few of the things they’ve taught me about teaching.

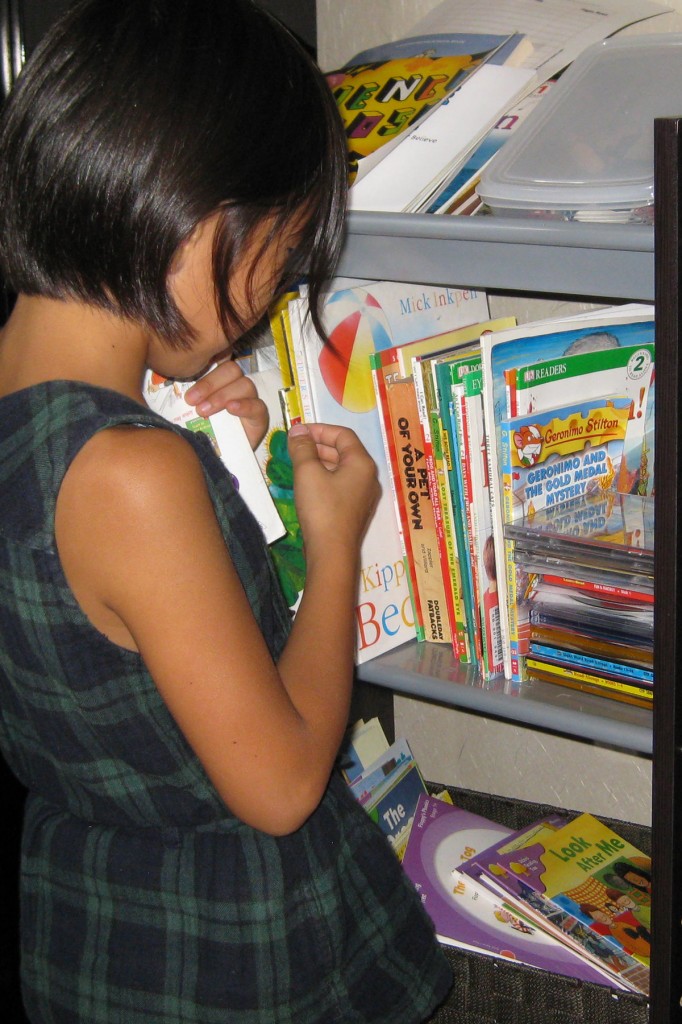

Nurture curiosity and creativity

Children are naturally curious, so encourage them to use English to ask questions and explore. “What’s this?” and “Why?” are very easy but powerful questions, and “I don’t know. Let’s find out!” is a great model for learning. Accept that there’s more than one way to look at things. For example, we often check comprehension by asking children to separate vocabulary into categories. If we put pictures of ice cream, spaghetti, a polar bear, a snake, a pencil, and a piece of paper on the table, we might expect groupings for food, animals, and classroom items. After students have done the expected task, ask them to create a new category of items and explain it. You might see milk, ice cream, polar bear and paper together (things that are white) or spaghetti, a snake, and a pencil together (things that are long and thin), or something else entirely. The point is to reinforce flexible thinking while building language skills.

If one of the aims of early childhood education is to teach what rules are and why we need follow them, then young learners are experts in the art of breaking them.

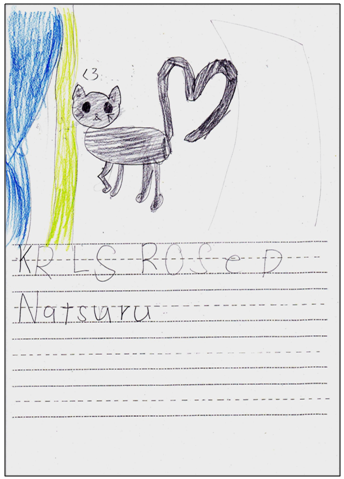

Focus on accomplishments

Young children are thrilled when they master a new skill or acquire a new word, and don’t tend to focus on what haven’t yet mastered or learned. Teachers have a tendency to see errors rather than accomplishments, which limits our ability to understand either one. In the example below, the student still has a long way to go in her writing development, but she’s already accomplished a lot. She has a good handle on her consonant sounds, is beginning to make some good guesses with vowels, has spaces between her words, and is writing from left to right. She can read what she wrote (“Kuro likes outside”), and is communicating something that’s meaningful to her (Kuro is her cat). Understanding her errors in the context of her accomplishments helps me to plan more effective lessons.

Sharing is another kind of showing, one that adds purpose to using language.

Show and share

Children nearly always show rather than tell. I’m almost always better off showing my students what I want them to do rather than telling them. I’m always better off showing them how language works than explaining it.

Observations can show me what’s actually happening in class (versus what I think is happening). One easy way to find an impartial observer is to set up a video camera in one corner of the room and leave it running for the entire class. I did this when I was having a problem with younger siblings disrupting class. What I observed was two young girls trying to join the older children and becoming frustrated when they couldn’t (usually because they didn’t know the English being practiced). Since the parents and students were all fine with the non-paying siblings joining, I turned it over to the students to set the rules. In the process, I got to see how students had interpreted my class rules. Beyond that, they came up with adaptations that enabled the younger children to join activities even without knowing enough English. I was impressed with the creativity and empathy my students used in solving what could have become a major classroom management issue.

Sharing is another kind of showing, one that adds purpose to using language. Technology makes it easy to share student projects with parents and other students. For example, my older students always need practice with writing and speaking clearly, in addition to opportunities to use English in meaningful ways. So, when my younger students were ready to take on English prepositions, the older students created listening tests for them. These student-made tests are motivating for everyone involved, and they encourage a level of care with enunciation that I can never achieve without an audience.

link: http://www.authorstream.com/Presentation/barbsaka-1551393-satoshi-listening-test/

To see an example of student projects, visit my YouTube channel or authorstream.

Children begin formal education unaware of rules that limit answers to a single correct response, that make errors more important than accomplishment, that put an emphasis on telling rather than showing, and keeping rather than sharing. By learning to break these rules in our teaching, we can also encourage students maintain healthy attitudes about exploration and sharing, and develop creative and critical thinking skills, in addition to helping them become skilled language users.

For example, the idea that teachers should incorporate techniques to reach different learning styles or multiple intelligences has been largely discredited in research studies. Not only is there no proof that teaching to different modalities is useful, there is evidence that it can be counter-productive. However, thinking in terms of learning styles is still a useful rubric for lesson planning, and getting teachers to see that they tend to teach in the way that they like to learn is a valuable step in encouraging them to experiment with different ways of presenting material. For many teachers, the idea that the same material can be taught in a variety of ways is new, and liberating. The idea that students process information in different ways resonates with teachers.

For example, the idea that teachers should incorporate techniques to reach different learning styles or multiple intelligences has been largely discredited in research studies. Not only is there no proof that teaching to different modalities is useful, there is evidence that it can be counter-productive. However, thinking in terms of learning styles is still a useful rubric for lesson planning, and getting teachers to see that they tend to teach in the way that they like to learn is a valuable step in encouraging them to experiment with different ways of presenting material. For many teachers, the idea that the same material can be taught in a variety of ways is new, and liberating. The idea that students process information in different ways resonates with teachers. Do I think all teachers should use learning styles as a rubric for planning lessons? Do I think all teachers should use rewards? No, of course not. What works with one of my classes may not even work with another of my classes, let alone another teacher’s class. Each group of students has its own dynamic, and requires a slightly different teaching style.

Do I think all teachers should use learning styles as a rubric for planning lessons? Do I think all teachers should use rewards? No, of course not. What works with one of my classes may not even work with another of my classes, let alone another teacher’s class. Each group of students has its own dynamic, and requires a slightly different teaching style.