Five Things I Think I Know about Writing ELT Materials

Barbara Hoskins Sakamoto

Like for many teachers, my first ELT materials were worksheets I created for my own classes. Sometimes I needed to supplement what was covered in the coursebook, sometimes I wanted to take advantage of student interest in a topic, and sometimes I had to create specialized curricula. The first materials I wrote for publication were guides to go with coursebooks. Eventually I started writing coursebooks. I’m still learning new things about writing and materials design, but here are five things that I think are important in creating excellent ELT materials.

Have a clear purpose

Even if you are only creating a worksheet that will be used once in your own class, you should have a reason for using that handout rather than doing something else. All materials should have a purpose and fit into the larger context of a course curriculum, or a coursebook syllabus. What are students supposed to learn? How does it build on what they’ve already learned and how does it prepare them for what will come next?

Aim for transparency

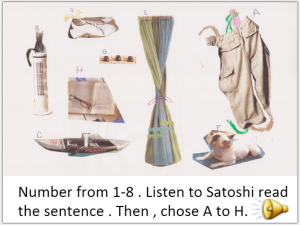

Teachers and students should know what to do when they look at your materials. If you’re creating worksheets for your own students, this might not seem very important because you can explain anything that isn’t clear. But what if someone else has to teach your class? Will your replacement be able to look at your materials and know what you had in mind? Transparency is essential if you are planning to publish and sell your materials. The easiest way to understand this concept is to browse through coursebooks at a bookstore or at a conference. Flip through books asking, “What are students supposed to do on this page?” There are plenty of good materials available, so teachers aren’t likely to choose books that require them to guess what the author had in mind.

Write a lesson plan or teacher’s guide

If you’re writing materials for your own classes, this might seem unnecessary. However, writing lesson plans to go with your materials, whether they are ultimately collected in a teacher’s guide or not, helps identify problems. Let’s say you’ve created an activity to have students talk about things that they have and things that they want. You might not see a problem until you write a lesson plan and realize that it might be difficult for students to differentiate between the two verbs. I want a new game and I have a new game are both grammatically correct, so you might end up spending your class time explaining the difference in meaning between have and want rather than practicing the language.

Get feedback (and maybe an editor)

After you use your materials in class, make notes about what worked and what might need to be changed. When students are doing a worksheet, notice how much help they need. Give your materials to a teacher who hasn’t seen them before and ask for feedback.

If you have any plans to publish and sell your materials, an editor is essential. No matter how brilliant your content is, a good editor can make it better.

Keep learning

I’ve been writing materials for more than 30 years and am still learning new things about writing, about learning, and about pedagogy. When I first started writing, an electric typewriter was considered high tech. Now I’m learning how to use online authoring tools for online lessons and how to write video scripts. The world of ELT materials writing is always changing, but the fundamental principles remain constant. If you want to improve your own skill as a materials writer, I highly recommend Katherine Bilsborough’s course, Creating ELT Materials 2019. This is the third year I’ve had the privilege of working with Katherine on her course, and I always learn something new from her.