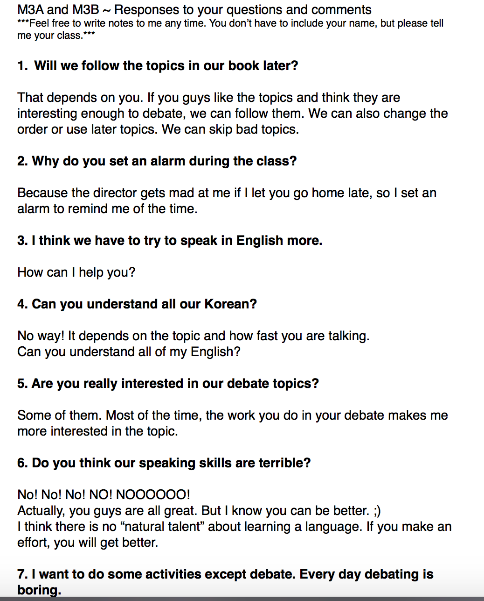

One Class Many Challenges – Anne Hendler

Staring at a blank piece of paper. That’s how I approach each class, every day during my prep time. What did we do last time? What did I assign as homework? It was just two days ago but it didn’t fit in my brain. Who didn’t make it to the class – did I remember to write it down in the rush of students coming and going?

I teach six or seven classes a day, with ten minute breaks between them. Ten minutes are barely enough time to catch my breath, write down the homework for the class that just finished, glance at the plan for the incoming class, and sometimes get a drink of water, so the hours I spend preparing for my classes in the morning are essential.

One of my teaching challenges is that, with so much going on at once and very little breathing space during the day, I have little time to reflect on my classes. As a result, I miss a lot. My perception of the class can be far wide of how the class actually went. One of the ways I am trying to solve this problem is taking a leaf from John Fanselow and recording my classes. I figure if I have time to watch the iTDi MOOC for an hour every night, I have time to listen to and transcribe parts of lessons now that the MOOC is over.

It’s 4:20pm. They storm into the classroom, chattering at the tops of their voices. Five boys and seven girls, all about ten years old. All of a sudden five kids are at my elbows: What was the homework? Did I do this right? I forgot my book/notebook/ workbook/ homework/ pencil. Can I go to the market? May I drink water? I did my homework! Check my homework first!

They sit in a large circle. Katie and Heather are in the corner furthest from me. They both have new glasses. Sarah and Cynthia are in the middle. Cynthia shouts rather than talks. Sometimes she shouts herself hoarse. My mom used to say I did the same. Charlotte is in the corner alone, always alone. She’s the youngest in the class. Next to her are Hannah and Alison. In the front are the bright, tiny Alex and his best friend Kevin. Chris is next – he never smiled or spoke before Kevin joined the class. Now he rarely pays attention to the lesson, but he is much happier. And on the far side are Jim and Jake. Jim is the oldest in the class. He rarely participates and doesn’t get along with the other boys, but won’t work with the girls. Jake does his best to get along with everyone. He has a birthmark that has turned one of his eyes electric blue.

Hello! I say, beginning the class. How are you? How are you Alison?

I’m happy and sad!

Why?

Happy is just because.

Sad is because in school we played a game (monkey in the middle) and I lost a lot and my friends sat on my feet. … How are you, Alex?

They ask each other in a circle. They talk about their school day, their homework, their high and low points of the day. Some of them remember new details and ask to have another turn. They help each other when they get stuck on words. Sometimes they end up all talking at once and the noise level soars to a glass-shattering pitch.

I walk around and check whether homework has been completed, making quick comments and corrections. Meanwhile the students chat. When I finish, I quiet them again and write the review on the board. Look at the board. … Alison, what did I say?

Review? Open the book?

Look at the board, please. Are you looking at the board?

I’ve written ten foods on the board without articles. What do you want to eat?

I elicit answers from the students. They don’t have a/an/some down yet. I’d love them to learn these articles, but I know that with the absence of articles in Korean and the mere hundred minutes a week of practice it is not very likely.

Meanwhile Heather and Katie are leaning back on their chairs. The other students are quick to tell on them. Next time you do that, you’ll stand up. That goes for everyone. Another distraction.

I want to drink some juice.

Good, Cynthia.

Ah, Anne? I want to use a tissue. Very dirty.

Here you are, Alison.

Okay, look at the board. We go over the food words on the board and assign them articles and go over the rules (count, non count, singular, plural, consonant, vowel sounds). They got it.

Anne. Can use the bathroom?

No, not now. Now we’re studying. … Heather, what are you doing now? … Okay, open your student books to page 65. Look at the pictures. They go over the images in the book and use them in sentences.

I’m hearing this: I’m hearing ‘I want eat a banana.’ I write it on the board.

No! to! to!

Right. I want to eat a banana.

They do it right next time. And again and again.

Alright, you’re going to work with your partners. Today’s partners are….

I assign the partners. They ask each other what they want to eat. I monitor, paying special attention to Heather and Katie, who are probably not doing it, and Jake and Jim, who seem awfully quiet. Suddenly I look up and see Chris slap Kevin across the face. *Blink.* Chris! Out. He goes. Kevin looks stunned. The students continue with the exercise. I go out to Chris.

Why did you slap him?

He slapped me first.

Are you fighting?

No.

Playing?

No.

*smh*

Never do that again, okay?

Yes.

I send Chris back in and ask Kevin to come out.

Did you slap him first?

Yes.

Are you fighting?

No.

Playing?

No.

(at least they’re consistent) *smh*

Never do that again, okay? Don’t hit.

Yes.

We go back in to a chorus of “May I go to the bathroom/ drink water/ not be in the room right now for whatever reason?”

No. We have to study now. Because whoever wrote your coursebook thought that “I want” and “I like” go really well on the same page when the focus is a/an/some, I say inside my head.

We practice. Cynthia is yelling so loudly she starts coughing.

Students shoot each other ‘do you like’ questions.

Do you like doyou? [soy milk, in Korean]

Yes, I do. Do you?

Yes, I do!

I monitor the questions and the time. It’s getting late and time for our final activity – a restaurant role play.

Do you like obait? [Korean for vomit.]

No, I don’t. Do you?

No, I don’t.

Cynthia, do you eat obait?

No, I don’t. They make gagging noises.

From another corner: Anne! Anne Anne Anne Anne! What is soondae English?

I end the activity because the noise level has gotten out of control again.

Time to check the comprehension – with both types of question (What do you want? and What do you like?) randomly interspersed. They got it. But they weren’t finished – Anne! One more time!

Okay….

I like French Fries.

I want to eat some bulgogi.

I want to eat some chicken galbi.

May I drink some water?

No, you may turn your page, please.

May I drink some water?

May I drink some water?

What’s number 1? I ignore her. She just wants to get out as soon as we start using the book. Every time.

You are going to play the restaurant game. Listen up. You’re going to be in groups of four. Chris and Kevin, change seats with Cynthia and Sarah.

Endless groans. The play rock scissors paper for who has to sit next to a boy. The girls try to make sure the boys don’t touch their bags.

Choose a waiter for your group. Hey…. sit down! Shut your mouth. HEY. Listen. Each team choose one person as a waiter.

NOISE happens, but resolves itself into rock scissors paper. There are only five minutes left for the activity and I know it, but starting is better than not.

Waiter, your job is asking the question, “What do you want to eat?” Waiters, let me hear you!

“What do you want to eat?”

One more time!

“What do you want to eat?”

Thank you. Customers, your job is look at the menu and decide, what do you want to eat. You can say, “I want a…. chicken sandwich and some soup and some water, please.” Waiter, you have to take the order of three customers. THREE customers.

Ready? Start.

Sit down?

No, stand up.

Oh, I mean Stand up?

Yes, stand up.

The game begins. Alison circles the orders on the menu. Heather tries to do it without getting out of her seat. Charlotte tries to climb on the tables. Hey! This is a nice restaurant.

Alison begins by asking her customers how they are. She doesn’t finish taking orders. Heather passes off her waitressing duties to Katie.

I write the homework on the board while they are still doing the activity, but they drop the activity as soon as they realize it’s time to go.

Bolseo?! [Already?!]

And away they go. Did all that just happen in one class? What do I need to remember or write down before the next group begins? My head is spinning.

Not this kind of spinning.

[Fire spinning by @sandymillin – ELTpics – creative commons]

Luckily, this time I remembered to record the class. I don’t have time to transcribe more than I have just done. My impressions from writing this based on the recording, the transcription, and my memory of the class are that it wasn’t as bad as it felt to me at the time.

- There was a lot of conversation and a lot of English happening.

- The students all did quiet down when I asked for their attention.

- They were eager to do any activity I asked of them (although not necessarily with the people I asked them to work with).

- They tried. They made mistakes. They corrected their mistakes. They tried again. They succeeded.

- The face slapping was unexpected, but no one was hurt and no one cried and I managed to keep my temper.

- I felt like my brain was going to break, but it didn’t.

- The noisy periods when they weren’t engaged in anything were not as long (objectively) as they felt in class, and the periods that I thought were wasting time were also not very long and were more authentic uses of English than most of the class.

In the future, I think I am going to ask the students to check each other’s homework. I think I will also begin to ask them to write down directions in their notebooks. That might help keep them focused and keep it real.

I will record this class again and transcribe it. It was really useful to visit the class again after the fact. One thing I noticed today that I didn’t notice during the class was Alison’s (clearly intentional) use of TL when she asked for tissue.

Things I wish I had done differently:

- paid attention to what kind of noise there is in the class, rather than just the volume.

- paid attention to how language is used in the conversations that were not based on the book.

- allowed Cynthia to drink water.

- figured out what was up with Chris and Kevin and the slapping.

- started the restaurant activity earlier and skipped the ‘do you like’ part.

I don’t have time to do this more than once a day, so I think I will make this class my project for a few weeks and see if I can change the way I see what happens in the class and slow my brain down a bit.

Not this kind of spinning.

Not this kind of spinning.