A magical, musical path

– Nina Septina

Music is the language of the universe. It links people all over the globe by breaking limits and going beyond boundaries. It’s all around us, it’s in the atmosphere. No one can avoid music communicating through their heart and mind, speaking to their souls. Life has given meanings to songs they sing. Many people can’t live without music; I am one of them.

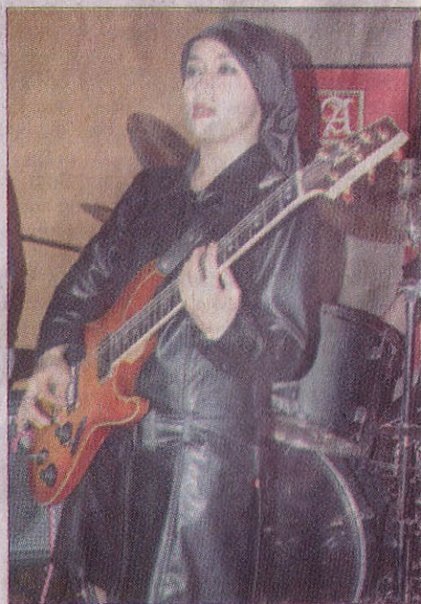

Music has greatly influenced me throughout my English learning history. Listening to English songs a lot, trying to sing along with them, writing the lyrics myself, composing my own songs, and playing music in a band were some of the things I enjoyed doing while I was a teenager. Though now I have given up playing with the band, those musical experiences have contributed deep-seated changes to my English and shaped the way I teach my students. In class, music has always been good company for me and my students when doing activities. And finally this passion for music unexpectedly became my first ride on my professional development journey and brought me to a role I didn’t previously envisage.

It all began when I taught a group of university students back in 2009. Music bestowed its energy on bringing us closer together in our first meeting. The ice was melted as I played my guitar and asked them to sing along. Nonetheless, later on the next meeting I found out these students had a problem with their English pronunciation and fluency. Their unclear pronunciation made it difficult to grab the meanings of words they were saying. It was hard for them to even to say one single sentence smoothly. Pauses of hesitation were everywhere, making sure the intonation didn’t come out right.

I knew I had to do something. Knowing we had a common interest in music, I tried using its power as a way out of this problem. I reflected on my own musical journey and I believed that by engaging them with a “thing” that tickled their fancy they’d enjoy their learning more! Another consideration was the plausible theory that songs present opportunities to improve pronunciation and accelerate fluency, which are the main cognitive reasons for using chants in language classrooms.

Thus in almost every meeting we had a special session for around 20-30 minutes where we sang English songs together. I started it with an easy pop song and continued giving them more challenging songs with more vocalizations. By varying the drilling techniques, students didn’t get bored. On the contrary, they seemed enthusiastic. Furthermore, they would leave the class humming or singing the song we practiced. Some students also told me that they couldn’t help singing the songs outside the class as those melodies and lyrics got stuck in their heads. I said to myself, wow, they drilled the language themselves, effortlessly! They could remember the lyrics, the chunks, and the intonation patterns fast. The repetitive exercise gave them the chance to memorize both words and pronunciation well.

At the end of the term, I distributed questionnaires to see how students perceived this treatment. The results revealed that students were pleased to be able to sing in class. This, according to them, had revolutionized their usual classroom routines; they also stated that their English had improved, especially in terms of pronunciation and fluency. And furthermore, students demanded to continue this singing treatment in the next term. In addition to this, I also observed their progress reports and was startled when I saw they could really make an improvement in their pronunciation and fluency as shown in the average class scores.

My supervisor encouraged me to put this case into a research paper. This was quite a challenge to me, as I had never done anything like this before. Moreover, hitherto I found writing as the most challenging task for me compared to the other skills. However, I took up the challenge and I made myself believe that this would be as challenging and at the same time intriguing as writing a music piece, and I would enjoy this as much as I musically enjoyed writing verses for my very own song.

Eventually I finished my first research paper and it got accepted for a presentation at the TEFLIN International Conference. At this conference, I met some inspiring people who then escorted me to see the bigger world. A world of wonders in which I could meet many more great people online and offline and build my PLN. This was something I had never imagined before. My musical journey has brought me here, on a pathway where I’ll go, grow and glow with others in iTDi, becoming a better me, personally and professionally. – Nina Septina

Connect with Nina, John, Marco, Steven, Alexandra, James and other iTDi Associates, Mentors, and Faculty by joining iTDi Community. Sign Up For A Free iTDi Account to create your profile and get immediate access to our social forums and trial lessons from our English For Teachers and Teacher Development courses.

Like what we do? Become an iTDi Patron.

Your support makes a difference.

Nice post Nina. What I have noticed in my practice though when bringing music into the classroom besides the general enthusiasm, the motivation degree, the apparent easy access to the language, the fluency level, the capacity to retain the lyrics demonstrated by the students , there’re a question that has always got me puzzled and to my shame could never and still can’t find the answer: why do struggling students who have memorised tons of English lyrics, sing and rap in almost excellent and fluent English still find it very hard to hold a conversation in English and speak without stuttering? It seems as though when the rhythm is removed said- students are suddenly stripped of their fluency skills and revert to their earlier state. That’s very frustrating to the students as well as to the teacher. I wish I could find the answer to this puzzle.

Dear Rima, Thanks for taking some time for reading my post and leaving your comment and question here. You’re absolutely right, I also find many similar cases where students often get stammered when holding a conversation or giving a talk, but quite fluently when singing. This also got me puzzled, frankly.

However, looking back to my own experience on how I gained fluency, by singing not only I enriched the vocabulary and the meaning of words but I also learned the pronunciation and noticed how those words used in many contexts. From there, when I got into a conversation and had to respond to the chat at that particular moment, those retained memory of word pronunciation and the knowledge about the meanings and the functions were quite helping when I got to construct new sentences in different contexts. So there’s a transfer from the existing knowledge to a new learning experience, and this linking process could help me with my fluency.

Since this is a quite interesting topic, I also sent your comment above to a good friend of mine who’s an expert in this field, Tim Murphey, and this below is his response :

Memorizing things only helps when they are converted by use in particular contexts. If you have memorized my phone number at a point in time, but never really called me, it fades from memory. Furthermore things that are used a lot in one context, like songs being sung by a band or in karaoke, are difficult to operationalize in another without practice. In theory once you know how to drive a car, you should be able to drive on anywhere, but it is a very different task if you have never driven off road, or in steep mountains, or on the opposite side of the road – some skills can transfer but there is also new learning that is needed.

One thing teachers can do is to ask students to bring their song lyrics (if they are not too full of bad words) to class and to operationalize them by using the words in stories and conversations. One song I teach for example has a line “the world is so fascinating” and I ask my students to tell their partners three things that they are fascinated by in their lives, which is operationalizing/activating the vocabulary item so they can use it in every day life.

If it just stays in the context of “This SONG” it may not automatically transfer, just as driving in Florida flatlands is very different to driving around Davos, Switzerland, or in a car race.

OK, Rima thanks again, hope this helps with the puzzle 😉

Thank you very much for replying to my comment Nina and thanks to your friend too! Really appreciate it.

I’m glad you mentioned your own experience with learning English and you stress the contribution of music to the improvement of your fluency skills, pronunciation skills and vocabulary enrichment. You were a good student Nina, weren’t you? My point is I never disagreed about how helpful and useful music can be and I’m sure you might have noticed in my comment the use of the word ‘struggling’ students. It is precisely this category that caused my frustration. I couldn’t understand how the transfer is quite automatic for the well-achieving students and not for the others. And it is mostly the case of one particular student who left me dumbfounded: he’s a rapper and has memorised hundreds of songs, raps in excellent English but when he tries to speak, he’s unable to utter a single sentence without stumbling over his words; It made me feel so bad. I should’ve helped him more with his transfer skills, I reckon. But he’s no longer in my class now; he’s left.

Thanks again Nina for your help.

Rima

Hi Nina,

What a fantastic post. It’s great to hear about teachers who are doing things in a classroom I could never have imagined on my own. Your story of using songs for fluency practice has me thinking about how I can also bring more music into my own high school classroom. Thank you.

Rima, I just thought I would jump in here. I’ve also found that teaching a song doesn’t automatically lead to students being able to recover and use those chunks in regular conversation. I used to use music a lot when I taught with children and I found I had to take the language in the chants or songs and have the students practice it in a more conversation style many many times before there was a transfer between the chants/songs and conversations. That being said, I stil felt like the students were improving more quickly than if I left out the chants/songs from the lessons.

It would be a very cool piece of research to see if chants/songs reduce the amount of times students need to attain fluence for certain phrases or even grammatical structures.

Thanks again Nina for a great read and much to think about.

Kevin

Hi Kevin, Thanks a lot for your response! 🙂

And I do agree with you that teaching songs doesn’t automatically lead to students being able to recover and to use the chunks in regular conversation. Surely it needs more than that. Singing means memorised speech and conversation means spontaneous speech, when we sing we know what we’re going to say but when we’re in a conversation (which we have to respond spontaneously) we have to rely on our linguistic resources : vocabulary, grammar, etc and students need many exercises to gradually get this established.

So again I agree with you that it needs time to allow a transfer from the chants/songs to the conversation.

Thanks again, Kevin, you also wrote a wonderful post 😉

Thanks Kevin for your insightful answer.

I too am looking forward to a research study that would investigate whether music helps learners achieve fluency skills. Can’t wait to see the outcome of such a study.

Rima

Just wonderful experience. Once, I encouraged the Students to create sentences using rap music. The result is over my expectation. They were very creative and more productive in learning Grammar.

Thanks Indroyono, and happy to hear that the rap songs did work in you class! And I’m interested in knowing more on how you conducted this activity so that your students were more creative and productive in learning grammar. If you like, besides sharing it here, please also share your experience in our social forum in iTDi website, I’m sure many of iTDi members will learn a lot from you 😉