No One Has Special Needs: We All Do

I was a ‘special needs’ kid at school according to modern definitions. Nobody, including me, knew it at the time though. I wasn’t diagnosed until the age of 38. When I was finally diagnosed, a lot of my school experience starting making a lot more sense.

At the age of 14, I had another two years of compulsory French classes to attend, and the idea didn’t enthral me. But, in the first French class at the start of the new school year, my French teacher addressed me personally: “You can sit at the back of the class and talk to your friend Dave about any topic you like in English. However, do it quietly because the rest of the class will be learning French”. And, that’s what I did for two years. Needless to say I failed the French exam.

The irony is that I was probably one of the most motivated people in the class to learn French. If my teacher had asked me at 14 if I actually wanted to communicate in French, I would have responded with an enthusiastic ‘Oui’. If he had then asked me why I wanted to learn French, I would have explained that my primary motivation was to talk to teenage French girls on my family trips to France. Thus, I required conversational ability to cover the topics of music, fashion, etc. But, we never had that talk.

So why did I fail at French? Two main reasons: 1) The course. The classes were heavily grammatical and had no conversational component. Thus, the learning was perceived as not matching my goals. 2) Me. With hindsight, my ‘special need’ made me incredibly intolerant and outwardly frustrated in any situation that is not furthering my personal goals.

When I became a teacher of English I was determined to have conversations with individual learners about their personal goals, and spent effort on developing methods of analyzing needs. I became aware of teacher assessments that asked students to rate the class without probing for any personal circumstance. Thus, I would read a negative comment from a student about another teacher’s class, but, in a follow-up question directly to that student, the student would readily admit that the class wasn’t a success for that individual due to a personal health issue. According to the biased assessments, the school owners were ready to blame a teacher for a student’s personal problem. I changed the way class evaluations were structured.

A book that had a profound influence on my teaching was Psychology for Language Teachers (Williams and Burden 1997), particularly the chapter on teacher beliefs about learning and learners. The authors quote sociologist Roland Meighan (Meighan and Meighan 1990) saying that teachers beliefs about learners can be construed metaphorically as:

- resisters;

- receptacles;

- raw material;

- clients;

- partners;

- individual explorers;

- democratic explorers.

From my own French-learning experience, I knew I would never construe learners as the first three metaphors. As my teaching and teacher-training developed, I wanted to move from a construct of learner as partner (with the teacher) or as individual explorer to a belief that each learner in the class is a democratic explorer, but I was struggling for inspiration to make this happen.

The turning point was having my ‘special need’ diagnosed by doctors. This led to experimenting in professional groups I joined with explaining my behavior did not necessarily reflect how I felt about working in the group. I encouraged colleagues to challenge me if they felt I was being negative but didn’t mean to be. This approach worked well and helped me realize that we all have responsibilities as part of the group.

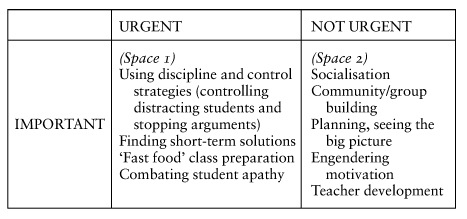

In the excellent book Group Dynamics in the Language Classroom (Dörnyei and Murphey 2003), the authors urge teachers to invest more time in the IMPORTANT/NOT URGENT (Space 2) activities. They say: “Learning about group dynamics and organizing well-functioning groups will go a long way toward facilitating smooth classroom management and enhancing student performance.”

(From Dörnyei and Murphey 2003:p11)

I agree with them. Every member of the group has a responsibility to see its holistic nature and have positive intention for the group’s success. I have gone full circle. It was not my French teacher’s sole responsibility to extract my learning preferences. I had spurned an opportunity to explain what I wanted and negotiate with the class.

We are all special and all have special needs. In a group, we have to make the other members aware of what these needs are and be able to position them in relation to everyone else’s.

“un pour tous, tous pour un”

References:

Dörnyei,Z.. and T. Murphey. 2003. Group Dynamics in the Language Classroom, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Meighan, R. and J. Meighan. 1990. Alternative roles for learners with particular reference to learners as democratic explorers in teacher education courses. The School Field, 1(1), 61-77.

Willams, M. and R. L. Burden. 1997. Psychology for Language Teachers. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press.

Great stuff Gareth. Interesting that I had a similar experience with French. It always struck me as odd that in French class I was considered the disruptive element and largely ignored but in Maths class I was the star pupil. It is clear now, though it was less so then, that the Maths teacher knew how to engage my interest and attention and the French teacher didn’t. This was probably not true for all students. There may have been students who were engaged in French and not in Maths. (I wouldn’t have noticed them!)

What often happens is that teachers teach to the lowest common denominator – they teach to the group that are, for whatever reason, willing participants. The rest get sidelined.

The challenge for teachers is to attempt to achieve engagement with all students. This requires a negotiation so that the needs (special needs?) of all students are being met on some level for some part of the class – i.e. a shift towards students as democratic explorers.

To some teachers used to meticulous lesson planning and a rigid class dynamic, the idea of having the students negotiate the content and direction the class takes may seem like a recipe for chaos in the classroom.

But as Deepak Chopra says “All great changes are preceded by chaos”.

Thanks, Mark. Remember our boss used to say “If I need to know what Gareth and Mark think, I only need to ask one of them”.

I hadn’t seen the posts from my co-authors on this ‘Special Needs Issue’ of the blog, but it’s a clear message of open communication from everyone, not just the teacher, although the teacher does act as catalyst. If teachers are unwilling to let go of rigid control and top-down planning, we need to explore the reasons. Quite often we find that these are related to external pressures of boss and assessment. I’m reminded of the demo class I taught at a British Council school as part of a job interview. I was told that the class had a few difficult students who refused to engage with any other learner. They would only engage with the teacher. The observers, directors of the school, were amazed that I had created such group cohesion and that all students were interacting with each other. The observers were distinctly unimpressed that I hadn’t achieved all of the (narrow) linguistic objectives set out by the textbook, and I was rejected. Thus, the tension is always going to be between what is best for each member of the class as negotiated in class versus what external pressures are being applied.

So nice to read your voice in this topic Gareth, even more wonderful to know you better.

Thanks for the post and it speaks to me in so many ways.

🙂 Rosie

Thank you for dropping in, Rose. Sweet as always!

I really like the way you take care to point out that accomodating a student is a two way street. The teacher has a lot of responsibility but can’t do it without the student being ready to accept help. Building THAT understanding comes first.

Great post!

Naomi

Thank you, Naomi. Your expertise in this area far exceeds mine. Group Dynamics in the Language Classroom contains a lot of practical advice on building understanding. My philosophy is to see all encounters as mirror reflections of myself. If there is something I do not like about a situation, what is it that I must do to change it? I work on breaking down illusions of separation and dispelling the idea of blame. Usually works.

Have you learned to speak French? Do you know of TPRS (Teaching Proficiency through Reading and Storytelling)? Based on Krashen’s Comprehensible Input, it addresses the needs of all students to communicate in a meaningful way about things that are important to them. I am currently using it with several special needs students and they are engaged and motivated by their success.

Hi Judy, No, I never learned French, but I did have a Parisienne girlfriend for a while. I haven’t heard of TPRS, but I will look it up. Thank you. I reached a reasonable level of spoken Japanese when I lived in Tokyo and have an intermediate level of Thai. I learned both languages by sitting down and talking with people.